Almost a year has passed since I did my Sea deep dives, and a lot has changed with the company and the market environment in that time. Over that time I’ve also had a lot of conversations with investors who I respect which has led me to further refine my thinking and approach. The biggest changes that have occurred are essentially as follows:

In a matter of three quarters the company went from one focused on growth at almost any cost to one focused on profitability, in part because of market conditions, in part because of the natural slowdown of its key businesses as the COVID-induced bump is digested. The significant organizational and cultural change that this requires is not to be underestimated

Garena: Clearly the segment where my forecasts were most wide off the mark. Forecasting any gaming business is inherently difficult even in normal times, and when you add COVID to the equation the results are even more messy. It’s clear that the COVID boost proved to be transient and now the business’s cashflow will be reduced from its 2021 peak of $2.8bn to somewhere between $1bn to $1.3bn, depending on where it finds the floor.

Shopee: The business went into 2022 with some rather ambitious growth targets despite the reopening headwinds which were already being felt in the region. As the year went on it became clearer and clearer that they were not going to meet these, leading to the inevitable guidance pull and perhaps some denting of management credibility. Shopee continues to have strong long-term potential, but the next year or so are quite uncertain as it struggles to balance growth and a pivot to profitability

SeaMoney: I think this business has been a bright spot, outperforming my revenue forecasts by some margin as the loan book is growing at a faster clip than I expected, and it’s expected to reach profitability sooner as well. However, I think there isn’t enough appreciation of the capital intensity required to grow this business. The majority of the loans are funded by Sea’s balance sheet, and there are regulatory capital buffers that need to be in place for the digital banking businesses - including potentially an additional US$1.1bn for the Singapore digital banking license - all of which further ties up valuable cash reserves

Finally, the big issue threading everything together is that the costs across the business are running at a far higher rate than I expected. On top of that, there has been a material increase in capex, which further adds to the cash burn. All of this leads to the next point

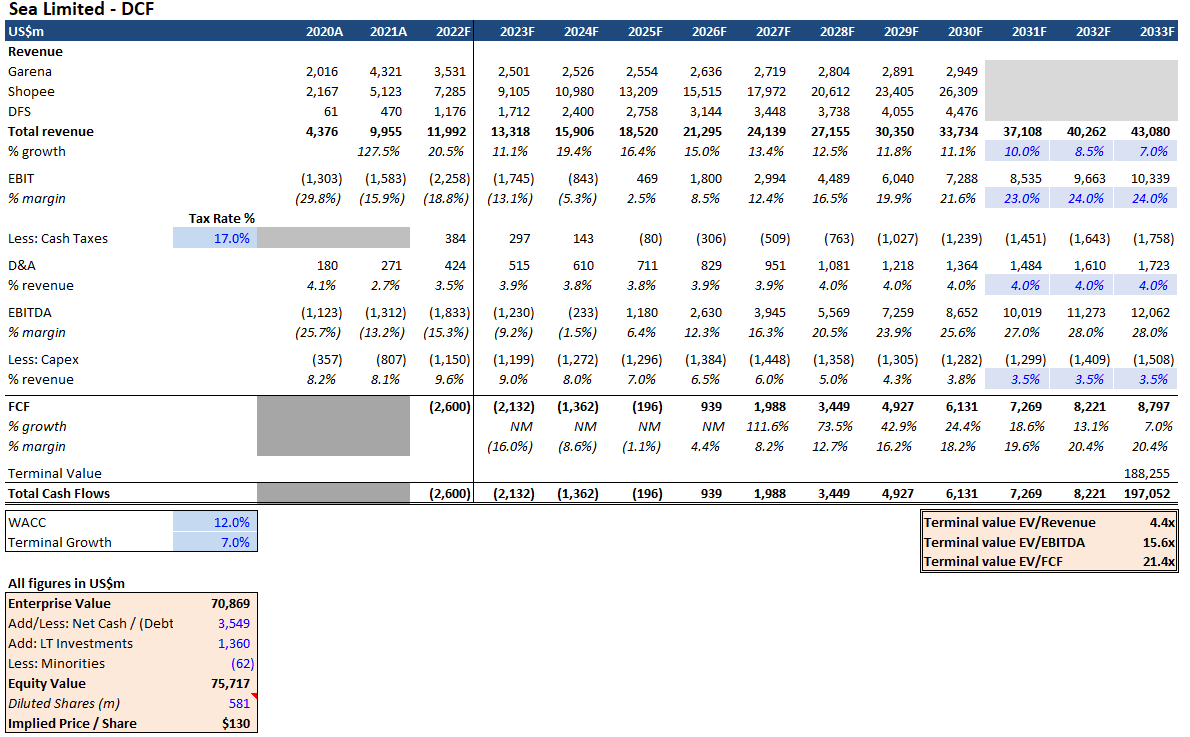

The biggest change I made is re-cutting the valuation methodology to a long-run group level DCF instead of the sum-of-the-parts paired with revenue/gross profit multiples. While the later is still favoured by sell-side analysts, I feel like a DCF, despite its subjectivity and complexity, is the only reasonable way for me to capture the cash flow situation of the business and anchor the valuation to something more tangible rather than just revenue. This requires some long-run projections to a point of “steady state” before applying a terminal value - I’ve assumed 2033 given the potential long runway for growth in this business. Of course the folly of making forecasts that far out is not lost on me, but this gives a good sense of what you to need to believe the business could look like to justify a particular value. This change had by far the biggest impact to my overall valuation

TLDR: I believe the fair value could be somewhere in the $100-150 per share range (or c. $50-80bn enterprise value) when discounted to today at a 12% discount rate. At the current price of $63 this implies IRRs of over 25%-30% over the next 5 years. If I had to be fair however, I would characterise this scenario as one where a lot has to go right for the business to earn this valuation. There are significant risks that need to be navigated over the next few quarters/years. If losses are not reduced fast enough I think liquidity concerns will emerge and they will need to raise new capital sometime in the next two years, especially with $3-4bn of convertible notes maturing over FY25/26. I’d be hesitant to buy until I see evidence that they have started to reduce the cash burn materially over the next few quarters. If this doesn’t happen, the stock could see further downside still from here. Investors need to make up their own mind on whether they think the upside is worth the risk. As for me, I’m still holding the stock, but you should do whatever is appropriate for your own personal circumstances and risk profile. None of this is investment advice. I’m just a retail punter who is doing this as a hobby.

H/t to my buddies Farrer Wealth, Art Capital and Chad for the many discussions over the last few months which have helped me shape a lot of the thinking and numbers in this piece.

I will run through some thoughts on each of the businesses and then come back to the overall valuation at the end.

Garena

In my Garena article I made a case for why I thought Free Fire would be a lasting franchise. I think the case for this still stands and the game will have a reasonably long life, however what I didn’t expect is that it would be off a much lower earnings base. I failed to anticipate three key things:

The COVID hump and subsequent normalisation, which I think is now well understood

The geopolitical risk around India and the ban that occurred early this year

The disproportionate impact that the US would have on Free Fire revenues over 2020-21, and this market would be a lot more transient vs. the rest

This third point on the US is worth expanding as I don’t think it’s fully appreciated by investors. During 2020-21 Free Fire started to really take off in the US, and between Q2-Q4 of 2021 Sea started reporting it as the highest grossing battle royale game in the US. This was important because the ARPU for US gamers is many times higher than that any of the developing markets like Southeast Asia, India and LATAM:

So despite its relatively low player base, US had a disproportionate impact on bookings. The following data is from SensorTower, and it shows how much of Free Fire bookings were coming from just the US market alone

We can also see that just as quickly as US revenues came, they also started declining much faster than the other markets (which are also declining but not to the same extent). I don’t think US was ever really a target market for Garena, and it was perhaps a fluke that they happened to do well there at all for this brief period. One way to look at it, is that by complete chance the US market came along and distorted the trajectory for Free Fire which would have otherwise been much less extreme both on the up and the down. Hence why I think there is still a valid case to be made for Free Fire’s longevity in the developing markets for which it was always intended. As the below data from activeplayer.io shows, the game is still pulling in a massive 290m monthly players and is the second most popular game in the world after PUBG. The player numbers are now running somewhere near the early 2020 levels. We can also see below that its peers have been declining as well, so this is an industry wide effect. I would still expect active players and bookings to continue trailing off over time given the natural life cycle of the game (Free Fire is now over 5 years old), but at a slower pace than this year.

What the management team did brilliantly however, was seize this moment of peak Free Fire performance in 2021, and raise a massive $6bn in capital, helped in large part by the frothy market conditions at the time. This has proved to be incredibly prescient and fortunate as it bought them several more years of runway.

So as for my revised forecasts, I have assumed the following:

FY22 bookings land at $2.9bn, at the bottom of their guidance range of $2.9-3.1bn. For the 1H of 2022 they seem to be tracking in line with that

FY23 bookings to decline by a further 15% to $2.5bn as new games will take time to ramp up monetisation. From there on I hold bookings largely flat (just growing with inflation) assuming that continued Free Fire erosion is offset by contribution from new games. There’s an overall assumption here that Garena will not just let the Free Fire franchise die, given how low odds it is to get a game of this level of success. I can see them launching spin-offs or sequels in the future to keep it going.

For EBITDA, I’m assuming margins normalise at the 47% level in FY22 and hold constant from there. While this is significantly lower than the peak margins of 60% in FY21, I think it’s still a generous assumption as these are the highest margins in the gaming industry. This results in ongoing cash flow of about $1.2-1.4bn going forward. As a cross-check, FY19 EBITDA was $1bn, so I’m assuming Garena gives back just about all of the COVID benefit

Very clearly what I’m not assuming here is another massive hit. Gaming is a creative endeavor where luck plays a major role in achieving success. So far outside of Free Fire Garena has shown limited ability to have success in self-developed games. I am also not forecasting Tencent to change the status quo with respect to their distribution agreement which remains a possibility ahead of its expiration in 2023. They may achieve another hit with a Tencent co-developed/published game, like Undawn which was announced last year but seems to have been perpetually delayed, but still the revenue and profit contribution from these would be about half that of a self-developed title like Free Fire.

Shopee

The major dynamic that Shopee is now navigating is the aftereffects of the huge ramp in Southeast Asian e-commerce penetration during 2020-21. Online penetration is probably much higher than people appreciate, and no longer is it correct to be underwriting single-digit penetration figures as part of a long thesis for Southeast Asia e-commerce. The Morgan Stanley data below I think does a decent job at showing how much of a ramp there’s been in ASEAN e-commerce (the teal dotted line). According to their numbers it went from 7% of total retail in 2019 to 20% in 2021, now only a little bit behind the more developed North America and Asia (i.e. China) markets who are in the mid-20s. It is expected to keep growing over the next few years of course, but at a much lower rate.

There is more nuance to this however. About half of the retail market is groceries and fresh food, a segment which according to the Bain/Temasek 2022 SEA report has low single-digit online penetration due to its expensive requirements for cold chain logistics. I’ve seen some estimates suggesting that the non-grocery segment (where Shopee predominantly plays) has probably over 30% online penetration, which would make sense as non-perishable goods lend themselves well to e-commerce. This implies that the non-grocery segment that is relevant to Shopee may grow even slower than the overall e-commerce TAM given its much higher penetration.

From a market share perspective, Shopee has done an excellent job of building its lead over the competition over the last 2-3 years. Depending on the source for the market size, it is estimated to have between 40-60% market share, a position it seems to be holding even during this recent slowdown.

So when we consider the near-term ceiling on market growth, Shopee’s already dominant market position, and the macro headwinds, it is perhaps not surprising that its GMV growth this year has looked like this:

The competitive landscape has seen some evolution in the last twelve months. While Shopee’s lead over its traditional competitors Lazada and Tokopedia seems to be stable, little attention has been paid to emerging competitors, namely TikTok and Shein. TikTok has made it a mission to rapidly grow its ecommerce in Southeast Asia, and so far it seems to seeing strong traction with the company reaching $1bn GMV in Indonesia in 1H of 2022, a large jump from the $1bn GMV it generated over the entire 2021. The concern is that the categories that its format tends to favour, fashion and beauty, are also the categories that Shopee has traditionally skewed towards (c. 40-50% of its GMV, see my Shopee article). In China, TikTok has already reportedly captured as much as 30% of the fashion and beauty category. Shein is already a fashion powerhouse that has captured the world by storm, and its aggressively expanding in Southeast Asia, even relocating its founder, key executives and parent company to Singapore. As Rui Ma tweeted it is now also expanding into into other categories. In short, it would be reasonable to assume that at least at the margin these emerging players would impact Shopee’s growth.

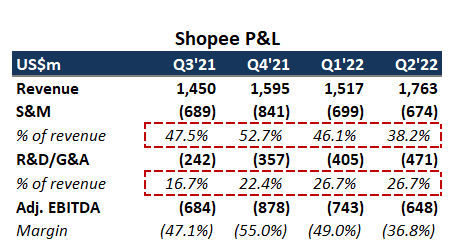

Turning now to the other key issue - unit economics and profitability. On the surface, Shopee’s unit economics seem to be moving in the right direction, with the company reported Adj. EBITDA ex-HQ costs per order for the SEA region almost at breakeven in Q2. The thesis I spelled out in my Shopee article around scale leading to pricing power (higher take-rates) plus some customer stickiness (evidenced by reduced S&M per order) seems to be playing out. As I tweeted post the Q2 results, while S&M has been under control, the concern right now is that the other overhead costs - G&A and R&D - have been exploding. These costs are currently running far higher than what I originally assumed, and are offsetting the improvements in profitability on the unit economics side. While my tweet was about the group level costs, here is what it looks like for Shopee alone - S&M has been coming down, but the other cost buckets have been rising fast:

The company would argue that these are investments in technology, product and people, which are essential for ongoing growth. However, the critics would argue that in the past Sea hasn’t been a company who’s been known for efficient, ROI-generating investments, as evidenced by the fact that they had to announce large layoffs across multiple markets and segments as a result of its past over-hiring, and shut down several new trial markets (France, Spain, India) due to too rapid expansion. As I mentioned at the start, going from a growth-focused company to a profit-focused company will require a massive organizational and cultural change, and it’s unclear how successful they will be in this transition and what effect it will have on morale. Hopefully we are past the peak of the cost increases however as the impact of these job cuts should start flowing through the P&L in Q3.

Finally, as I mentioned in my tweet I do have some concern around how their vague Adj. EBITDA ex-HQ costs metric by region gives them a lot of leeway to shift costs around between categories and segments to make the health of Shopee look better than it is. Sea’s complex reporting makes it easier to do this as well. Nonetheless, the final group earnings and cash flow numbers don’t lie, and that’s why I have now shifted my valuation approach to a group level DCF.

So as for my revised forecasts, I have assumed the following:

GMV growth breakdown upto FY25 as laid out below. This assumes Bain/Temasek 2021 SEA Economy report’s e-commerce TAM forecasts to FY25 (the source for most research analysts’ market sizing); some market share losses for Shopee (and taking into account potentially slower non-grocery segment growth); and some assumptions for Brazil+ROW which are growing at a much faster rate than SEA and drags the overall GMV growth rate up. From there I just steadily decline overall GMV growth to FY30

Take-rates continue to increase but at a slower pace than FY22. I have assumed that the marketplace take rates reach an average of 8% in FY22 (they were 7.9% for Q2) and increase to 12% by FY30. Total take rate (including 1P sale of goods) go from 9.4% in FY22 to 13.1% in FY30. This results in total revenue going from $7.3bn in FY22 to $26bn by FY30, a CAGR of 17%

S&M reduces from ~41% of revenue in FY22 to 25% of revenue by FY25, and eventually to 17% by FY30 (Alibaba is at around 12-16%, Mercadolibre is at ~20%)

Overall I have given management credit for their guidance that Shopee can reach EBITDA breakeven (post-HQ costs) for SEA in 2023, and complete “self-funding” by FY25 (which I interpret as EBITDA positive). By FY30 I have margins reaching c.25%, more or less in line with more mature e-commerce peers such as Ebay, Etsy and Alibaba.

Overall I believe these are not conservative assumptions, despite them being a bit lower than sell-side analysts. I have assumed that the company can both achieve reasonable growth (3.5x increase in revenue by FY30) and reach a healthy level of profitability over the long term. Whether Shopee can drive profitability without hampering growth is the big question right now, especially post the recent FY22 guidance drop. I have assumed here that they can deliver on both to a reasonable degree.

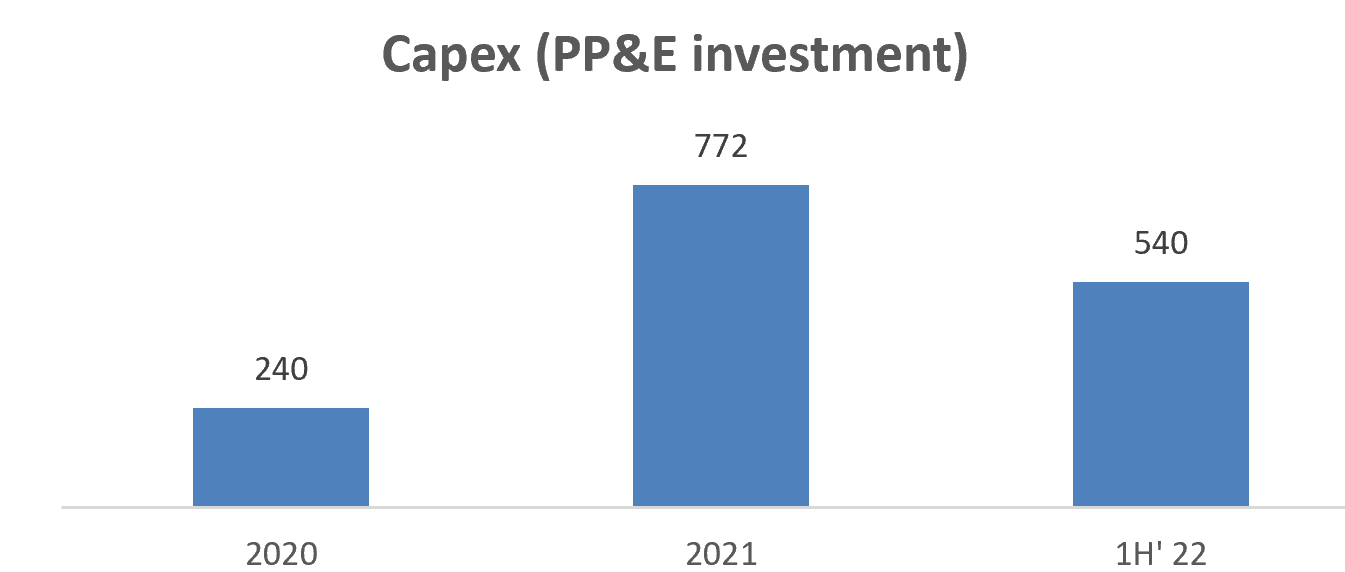

One more point around capex. Since 2020 we have seen a large ramp in Sea’s capex (or PP&E), which it defines as “servers, computer hardware, transportation assets, and land use rights/leasehold improvements” according to its disclosures. This amounted to $770m in FY21, and is run-rating at over $1bn for the full year FY22.

It would be reasonable to assume that a lot of this is Shopee-related given the company’s continued investment in Shopee Express, Brazil warehouses and Shopee headoffice in Poland. E-commerce is ultimately a logistics business. Getting goods from point A to point B requires real world infrastructure and assets, and the more of this Shopee controls the greater its ability to manage key customer pain points (delivery times, missing parcels etc) and drive efficiency in its cost base. We see the moat that logistics has created for e-commerce leaders like Amazon and MercadoLibre. Given how asset-light Shopee is currently vs. its peers, I have assumed they follow the same path and continue to spend this elevated level of capex going forward. Frankly I think that this is money well spent as a logistics moat will help them consolidate their position in Southeast Asia and would be something difficult for emerging competitors like TikTok to replicate.

SeaMoney

SeaMoney has been a bit of a bright spot in Sea, with the business outperforming my original forecasts at both the revenue and EBITDA level. This has been driven by the strong growth in the loan book which accounts for the majority of its revenue. There would also be some payments revenue from offline merchants recorded here, however most estimates are that this is not significant as majority of the reported Transaction Payment Volume (TPV) is related to on-platform Shopee payments, the revenue associated with which sits in Shopee (embedded in its take-rate).

I have revised upwards my forecasts to reflect this higher growth trajectory, assuming $1.2bn of revenue in FY22 (guidance is $1.1-1.3bn), and growing this to $4.5bn by FY30. I have also given the management team credit for their guidance of reaching profitability by FY23. Assuming credit losses are kept under control, this business has the potential to be quite profitable, especially as they bolt on new services such as insurance and wealth management. I have assumed it can reach over 30% EBITDA margins by FY30.

I wanted to make one more point on SeaMoney which is related to its capital intensity. The majority of its loans currently are funded from its own balance sheet, which is expected for a fledgling fintech business which has to prove out its lending and risk scoring algorithms before banks or securitisation partners would trust it to take loans off their balance sheet. In the 1H of 22 alone $757m of cashflow was invested in providing loans. Of course this capital is recycled as loans are repaid, but nonetheless this is like a very large working capital item that will tie up significant liquidity as they look to grow the lending business.

Further, as most probably know in 2020 Sea won a digital banking license in Singapore. One of the finer details in the 2021 Annual Report revealed that there is a S$1.5bn (US$1.1bn) capital requirement associated with this banking license, which looks like it hasn’t been provided yet given Sea hasn’t yet began its bank operations in Singapore.

I interpret this as if Sea wants operate as a digital full bank (DFB) in Singapore in the future, it will need to have at least that cash amount sitting on its balance sheet at all times. There will also be similar capital requirements for other countries where it operates as a digital bank (Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines) although none are likely to be as large as the Singapore one given the income disparity. Essentially it means that there may be well over US$1bn in capital that could be tied up to support these banking operations which cannot be used for operations or debt repayment.

Group valuation

The below DCF output summarises my overall projections for the three business segments, as well as capturing all the other corporate overheads and key cashflow items. As I mentioned in my tweet, there are other overhead expenses that do not seem to sit in any of the three core business segments, but are nonetheless running at very high amounts and thus cannot be ignored (these may be Sea Capital, Sea’s AI team, and whatever else they they are allocating to it). Also this assumes all share-based comp is fully expensed and treated like a cash outflow, i.e. no ‘Non-GAAP’ adjustments etc. I have ran individual segment forecasts up to FY30 as outlined above, however because free cashflows in that year are still growing at over 20%, I very roughly extended the group level projections beyond that to reach a point of steady state, which I assume is around 7% in FY33. By FY33 I assume the company is in a mature state, with revenue growth 5% and very healthy EBIT and EBITDA margins of 24% and 28% respectively.

I have included some other details In the footnotes here1 for those interested. One overall comment is that these numbers are more conservative than sell-side analysts, with street consensus for FY25 revenue and EBITDA of $27bn and $2.7bn respectively. I feel it is prudent to err more conservatively given the recent trend of brokers downgrading forecasts as Sea keeps disappointing, particularly on the cash burn. Nonetheless when you look at it holistically, I believe what I’ve modelled here is a very strong business, with revenue increasing 3.5x from FY22 to FY33 to reach almost $43bn (a CAGR of 12% for 11 years), and FY33 free cashflow of almost $9bn off the back of healthy profitability across all three segments. Frankly I would be quite happy if this is what the business managed to look like in the future.

Assuming Sea reaches steady state in FY33, I have applied a terminal value assuming a 12% WACC and a 7% TGR, both of which are a bit higher than normal given the business’s emerging market exposure. As a cross-check, this implies a terminal value EBITDA and FCF multiples of 16x and 21x respectively, which I believe are reasonable multiples to pay for a normal mature business. The resulting NPV is c. $70bn (enterprise value) or about $130p/s.

Of course DCF results are highly sensitive to a range of assumptions, particularly the terminal value, so below are some quick and dirty sensitivities to help get a sense of the valuation range

Key takeaways:

Based on this analysis, it feels like the fair valuation could be somewhere in the $100-150/per share range, or $50-80bn enterprise value (vs. the current enterprise value of $32bn at the $63 share price)

I struggle to see a path to over $300 per share again, unless for some crazy, unexpected optionality coming through like another Free Fire, or Shopee LATAM domination which sees its growth running far higher for longer, or just general market bubble behaviour

Liquidity and Financing

A final word on the liquidity situation. Below is a summary of the cash balance as well as short and long-term investments:

As at Jun-22 the company had $7.8bn of cash and short-term investments, which is down almost $2.4bn from 6 months ago. Based on my base case scenario in this article, I expect they may need up to another $4-5bn over the next 2-3 years before reaching breakeven. However there is also another $1.1bn potentially required to be put aside for the Singapore digital bank license as mentioned before (should they chose to go through with it), plus $1bn ear-marked for Sea Capital, although I expect that both of these, especially the Sea Capital funding, may be flexible should the situation require it. As can be seen then, there is a risk that their cash and ST investments starts running quite low in the next 3 years. There is also c.$1.4bn in long-term investments, however these are mostly investments in equities that are probably not easy to unwind (Sea Capital portfolio, amongst other things).

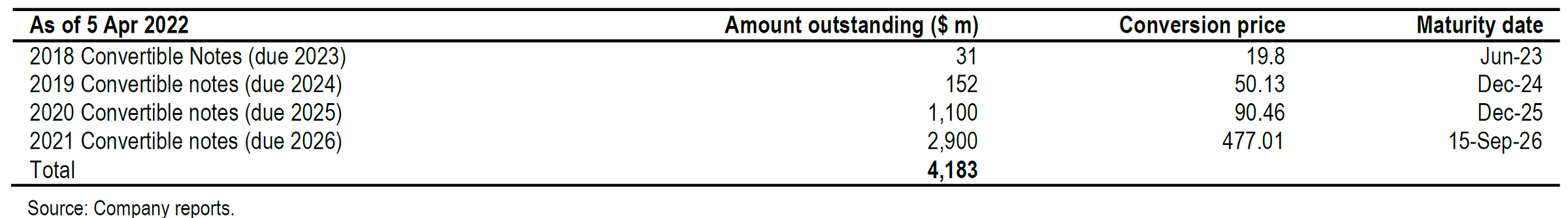

The below table summaries the convertible note maturities, amounts and conversion prices.

Almost $4bn of convertibles maturing in FY25/26 have conversion prices above current market price, however there is a good chance that the $1.1bn FY25 may end up-in-the money by 2025 given its conversion price of $90 (would result in an additional c.12m share dilution). Should it not be, repaying it may be possible but as per my analysis above, it would likely leave Sea with an uncomfortably low cash balance. The $2.9bn FY26 convertible is the big issue. Its conversion price is $477, which basically means it is impossible to see it convert to equity, and based on the current trajectory I see almost no chance of Sea having adequate cash reserves to repay it short of a completely drastic reduction in cash burn from here on in. That means they will need to hope for a better market environment to raise new capital to refinance it, which will almost certainly mean convertible notes with much lower conversion prices or straight equity - either way both may be quite dilutionary to current shareholders. Maybe they can raise another convertible which can be repaid years later when the company is making more cash, thus kicking the can down the road so to speak. Anyway these liquidity considerations are important to monitor and once again emphasise the need to start reducing cash burn immediately.

Concluding Thoughts

Perhaps needless to say, the spectrum of outcomes on a growth business like Sea is very wide. All of these forecasts are likely to be wrong, so readers should form their own view on what they think the business could look like going forward. The bulls for instance may argue that Sea may grow at 10%+ rates well past 2033 as it continues to evolve, invest in new business lines and generate optionality, which would of course lead to a much higher valuation. The bears may argue that there is no chance of the business ever reaching close to 30% EBITDA margins, leading to a much lower valuation. And while most people (myself included) tend to think and forecast in a linear manner, the world is highly non-linear and unpredictable, as the last few years have reminded us yet again. When I first invested in Sea in 2018 it was completely unimaginable that over the next few years the business would have the path that it has. We should always remain humble about our ability to predict how anything will pan out.

Finally, this article presents a long-term view on value, and I rarely speculate or have any insights on what could happen over the short-medium term. I would think however, that for Sea to have any hope of re-rating from its current trough multiples, it would need to demonstrate over the next few quarters that it has turned the corner on losses and started reducing the cash burn. While it’s hard to see the stock going back to the frothy heights of 10x plus revenue multiples of 2021, a couple of turns increase from the current 2.2x multiple doesn’t seem beyond the realm of impossibility, especially if the market environment also improves over the next year or so. Conversely, should the cash burn not start improving fast enough and liquidity concerns escalate, there could be even further downside from here. Either way, the next few quarters will be critical for management to prove their credibility and restore investor faith.

Thank you for reading. I welcome all feedback and for people to poke holes in my arguments as it helps test my thinking.

Historically the company recorded negative working capital which helped bolster its cashflows, mainly off the back of the bookings-GAAP revenue mismatch in the gaming business. This effect is unwinding now as Garena bookings decline, and I have assumed overall this will balance out over the long term and just modelled zero change in working capital. As mentioned in the SeaMoney section there will also be cashflow drag from growing the loan book which would offset any negative working capital anyway.

I’ve assumed that c.$180m of FY23/24 convertible bonds convert to equity and included in the diluted share count given they are ‘in-the-money’ (strike price of $20 and $50 respectively). The large bond issues maturing in FY25/26, $1.1bn/$2.9bn respectively, are currently ‘out-of-the-money’ given conversion prices of $90 and $477 (!!) respectively, so I haven’t adjusted the diluted share count for them. The FY26 issue will almost certainly never convert to equity given the high conversion price, but FY25 may certainly convert at some point in the next two years, which would increase the share count by 12m. See Liquidity and Financing section towards the end of the article for more details.

“Adjusted EBITDA loss per order before allocation of HQ-costs” is one of the most imaginative Non-GAAP figures that I have ever encountered. How far is the pathway to TRUE profitability after they reach breakeven on this adjusted level?

In Q4/2021 we were able to put together some pieces that could lead us closer to an answer for the above question. They reported gross orders of 2.0 bn, whereof more than 140 million were recorded in Brazil, i.e. the remainder of approximately 1,860 million were recorded majorly in the SEA/Taiwan region (ignoring minor markets like Mexico, Chile, and Colombia). Furthermore, for Q4/2021 they reported “adjusted EBITDA loss per order before HQ-costs below US$2”. Difficult to say whether it is closer to US1.99 or US$1.51. Let’s assume the middle point of US1.75 (Q1/2022 came In at US$1.52).

Q4/2021 adjusted EBITDA loss before HQ-expenses in Brazil is likely to amount to 140 million orders x US$1.75 = US$ 245 million. For the range of US$1.51-1.99, the adjusted EBITDA loss would amount to US$ 211-279 million.

In the same quarter, an adjusted EBITDA loss per order before allocation of HQ-expenses was US$0.15 for SEA/Taiwan. Multiplying this with the number of orders in this region, we come up with an adjusted EBITDA loss of around $US280 million. Interestingly, they achieve pretty much the same results both in Brazil and SEA/Taiwan, although the latter is 13x bigger than Brazil based on the number of gross orders.

Adding both, we end up with an adjusted EBITDA loss before HQ-costs of around US$490-558 million. Total adjusted EBITDA for the E-Commerce segment was negative US$878 million, which implies around US$320-403 million in HQ expenses!

In Q2/2022, the number of gross orders again amounted to around 2.0bn. If we assume the same number of orders as in Q4/2021 and adjusted EBITDA loss per order before HQ-costs of US$0.01 for SEA and US$1.42 for Brazil, we end up with an adjusted EBITDA loss before HQ in the amount of approximately US$106 million for both markets combined. As the total adjusted EBITDA was negative US$648 million, we can assume HQ costs in Q2/2022 of around US$542, an increase of 35-70 % compared to Q4/2021. This is mainly driven by the increase in other opex (R&D and G&A) in the E-Commerce segment which increased by around US$145 million compared to Q4/2021 according to my calculations.

The largest driver for breakeven on segment level is of course SEA/Taiwan. Assuming a steady-state for Brazil and HQ costs and the number of orders in both regions, adjusted EBITDA PROFIT per order before HQ costs need to come in at around US$ 542 million / 1,800 million orders = US$0.30 to breakeven on the segment level. The actual number would be lower when they bring down HQ costs and the negative EBITDA-impact from Brazil, i.e. increasing the number of orders disproportionately to the decline in loss per order in Brazil.

I think you tackled the decisive points phenomenally.

A lot of Sea investors have been feeling pain lately and clearly we had to adjust our investment thesis. It is much appreciated, that you tackle this directly with your well researched post and valuation.