Sea Ltd, Part 2: Shopee - The Everything Store of the Emerging Markets

Deep dive on Sea Limited

Firstly, just wanted to say thank you to the several hundred new subscribers who joined over the last few weeks. The response to the first part of my Sea Limited deep dive has completely surpassed my expectations. It’s great to have you all here. If you haven’t subscribed yet please consider doing so below or sharing with others who may enjoy this sort of content.

This second part will focus on Sea’s e-commerce business Shopee. In this piece I will cover the following:

Shopee’s blueprint for success

Competitive landscape - Lazada, Tokopedia-Gojek, Mercadolibre

An assessment of Shopee’s moat

The market opportunity

Pathway to profitability

Forecasts and valuation

Disclaimer: I am long Sea, and this article is not investment advice nor a substitute for your own due diligence. The objective of this article is to help formalise my thinking on the stock and hopefully provide some interesting insights on the business.

SHOPEE’S BLUEPRINT FOR SUCCESS

Shopee was started in 2015 as an adjacent business to Garena, however its origins actually came from behaviour that Sea management observed on BeeTalk, a chat app that Garena was building at the time. What they saw on the app was a large amount of peer-to-peer selling taking place, which gave them a crucial insight into the importance of C2C (consumer-to-consumer, or small casual sellers) in Southeast Asia e-commerce1. Even though BeeTalk was eventually shutdown, the insights and the technology from that venture got absorbed into Sea and led to the creation of a $100bn+ e-commerce business in the form of Shopee - a great example of how the company’s experimentation and innovation led to completely unforecastable value generation.

Sea’s CEO Forrest Li decided to have an ambitious young executive Chris Feng to run with this new business. Chris Feng was working in Garena at the time, but previously he was an experienced e-commerce veteran, having worked in Lazada where he was the Chief Purchasing Officer, and prior to that Zalora where he was the regional managing director (both are Rocket Internet companies where Chris was a managing director). By all accounts, Forrest Li lets Chris Feng run Shopee fairly autonomously. While Forrest will get involved in strategic direction setting, he really entrusts Chris and his team with the day-to-day running of the business. Both Chris and Forrest were highly focused on building up a talented and driven team and enabling them with an ownership mentality. The culture at Shopee is one that enables people with the freedom and autonomy to do whatever they need to do to win. This ethos transcends from Shopee’s headquarters in Singapore to each of the markets where it operates: from the onset Shopee set up local country teams who operate in a very independent manner and have a deep understanding of their market. This culture and the team have become one of Shopee’s key strengths.

Shopee was started as a C2C marketplace, but eventually evolved into a B2C/C2C hybrid model. The B2C segment represents professional sellers such as small and medium size businesses, and in 2017 it launched Shopee Mall, a premium brands marketplace which now has houses over 20,000 brands. Shopee still however has a relatively high share of its Gross Merchant Value (GMV) transacted through C2C sellers (~40%), much higher than other e-commerce platforms.

Most readers of this would probably be well aware of Shopee’s tremendous growth since inception; it is currently either number 1 or 2 player by market share in all of the Southeast Asian markets that it operates in2.

I couldn’t find similar time series data for Taiwan but we know that Shopee is most dominant there with around 52m monthly visits, followed by PCHome (32m), Momoshop (31m), and Ruten (30m).

One thing clear from the above charts is that the gap between Shopee and the others is widening in just about every market. While they were already doing well through 2019, it was during the pandemic in 2020 when Shopee really went for the kill. While its main competitors like Lazada were slow to act, Shopee accelerated investment and worked tirelessly with governments and its entire ecosystem to make sure that its business and its logistics fleet could operate during lockdowns. Only in Indonesia (the largest e-commerce market in SEA) is the race between Shopee and the local incumbent Tokopedia neck and neck, with Tokopedia passing Shopee in Q2’21 with more aggressive promotions and discounting.

Shopee however has been inspired by the success of Amazon, and is now increasingly becoming a global business. The success of Garena allowed the company to have a strong understanding of the LATAM economy. In 2019 Shopee entered Brazil where it has seen significant momentum, becoming the number 1 downloaded app in 2020. In Q1 2021 it extended its presence to Mexico, Colombia and Chile. More recently it has launched in other emerging markets - India and Poland - which the company is highly familiar with due to the success of Free Fire there.

Shopee relies heavily on its logistics and R&D offices in China, Korea and Japan. The overseas logistics offices in particular are important as they help drive the cross-border e-commerce trade which is a critical part of Shopee’s product offering particularly in the early stages of entering a new market.

The blueprint for their success in each region can effectively be boiled down to a handful of key components. While there is nothing really proprietary or irreplicable about their formula, it is the combination of Shopee’s clarity of vision, talented management team and excess capital (from Garena and the public markets) that has allowed them to execute on these elements so efficiently to scale quickly and build up a moat. This approach has been battle-tested and refined in Southeast Asia, and is now being deployed in LATAM and its newly launched markets of India and Poland:

1) Mobile-first strategy and highly localised approach

2) Cross-border merchants to scale up the supply side, and then add local merchants with low/no commissions

3) Focus on long-tail categories of fashion, apparel, health and beauty

4) Leveraging 3P logistics partners, and free shipping to accelerate the flywheel

5) Aggressive and creative marketing strategies through influencers and monthly promotions

6) Focus on customer experience, and increase user engagement through gamification and social commerce

Mobile-first strategy and highly localised approach

Leveraging the experience and knowledge from the Garena business which saw the proliferation of mobile gaming in emerging markets, Shopee was born as a mobile-first platform. It understood that mobile - not desktop - would be the main battleground for e-commerce in the future. This is quite different to its older e-commerce competitors like Lazada who began life as desktop versions and had to migrate to mobile over time. A mobile-native interface makes the shopping experience on Shopee well optimised for emerging markets which predominantly use mobiles to access the internet and shop online. Mobile share of e-commerce is significantly higher in Asia (70-80%) than it is in the rest of the world (~60%) and Shopee successfully tapped into that trend.

Southeast Asia is a highly diverse region with each country being unique in terms of culture, language, economic status of consumers, and lifestyle. Shopee understood this straight away and decided to operate a different version of its app in each market so that the experience is highly customised and fine-tuned to each market. For instance, in Indonesia and Malaysia there is a section dedicated to Islamic products, and in Indonesia the app has been tuned so that it works better on slower internet connections. Shopee invests significantly in the regions themselves through hiring of large local teams which have a good understanding of local markets. Local teams help drive localisation strategies at different levels, such as customised product selection, service portals, and marketing campaigns that are tailored to each market. Just to give a sense of Shopee’s commitment to the regions in which it operates, it has over 10K employees in Indonesia, double that of Tokopedia. All of these things help produce a superior customer experience, something Shopee is highly focused on.

Cross-border merchants to scale up the supply side, and then add local merchants with low/no commissions

When entering a new market, Shopee relies on cross-border merchants to provide the initial supply to the marketplace, usually wholesale merchants from China and Korea. Together with Shopee’s offering of aggressive discounts to customers, this helps drive traffic to the platform. Once demand starts being aggregated and Shopee gets initial scale, it is able to attract local merchant by offered subsidised shipping and no seller commissions. Lots of merchants in turn means cheaper products due to the natural competition that occurs between them, which brings in more buyers, and in turn more merchants, creating the network effect flywheel. This is quite a different strategy to Alibaba’s global business AliExpress, which is largely designed to be a cross-border business. For Shopee, the objective is to become a marketplace of local merchants, with the cross-border component just being the initial seed. If we look at Brazil as an example of a recently entered market, there is increasing evidence of this strategy working as according to management Shopee now now has more domestic sellers there than cross-border sellers.

Focus on long-tail categories of fashion, apparel, health and beauty

Shopee deliberately chose to focus on a wide range of lower-priced, fragmented categories such as fashion and beauty as a key differentiator from the competition. These categories tend to be highly differentiated with a large number of suppliers and large number of SKUs that sell in relatively small quantities due to fragmented demand. For this reason, a lot of e-commerce platforms, particularly ones with a significant 1P (direct retail) model such as Lazada, tend to ignore these categories and focus on larger-ticket categories with more homogenous products, such as consumer electronics, home appliances and FMCG goods. Long-tail fragmented categories like fashion and accessories allowed Shopee to build up a large assortment without having to take any inventory risk (high capital efficiency). A large seller ecosystem meant more variety of interesting products and also naturally led to more competitive prices due to the competition amongst sellers. Further, these sorts of low-cost items (e.g. $10 dresses) were perfect for Southeast Asian markets who are new to e-commerce and may not trust purchasing more expensive items.

As shown above, Shopee generates the highest percentage of its GMV from long-tail categories of fashion, and health and beauty, and baby products, compared to its key competitors. This brings a number of benefits:

These categories attract a younger female audience who tend to make more frequent purchases and in a way tend to be earlier adopters of popular culture. In contrast, consumer electronic categories which Lazada, Tokopedia and Mercadolibre are more heavy in attract a more male audience who shop less frequently

They have a lower basket size (Shopee’s average order value (AOV) is ~$11), encouraging more users to try the product and less concern over ‘fake products’ given the low cost. The more customers transact the more trust builds up over time

They tend to exhibit a lower tendency to ‘shop around’, since the products are differentiated and not overly expensive. This increases customer stickiness. In contrast higher ticket homogenous items like consumer electronics or home appliances (TVs, mobiles) tend to be price compared as they are relatively large and infrequent purchases, meaning the customer needs to be reacquired each time

The discretionary nature of these items means there is less urgency at getting them quickly (shipping times are not crucial)

These products are less penetrated in e-commerce compared to other categories such as electronics, providing Shopee with more room to increase its share

Finally, the margins in the value chain are higher are higher for fashion and accessories (less bulky/more compact transportation, differentiated products etc). Higher margins for merchants means higher take rates for the marketplace

These favourable characteristics of long-tail categories tend to create a stronger flywheel: they draw in more organic traffic, who make more purchases, which draws in more merchants and encourages existing merchants to invest more in the platform, which further increases the product range, leading again back to more organic traffic. Shopee structured its entire business around maximising this flywheel, and thus was able to scale quicker than any of its competitors.

Another important point is that while users start off using Shopee mainly to buy cheap low-end items, as they increase their frequency of use and get more comfortable with the platform, they naturally start to shift upmarket and buy more expensive items such as branded apparel and consumer electronics. This strategy is a bit of a trojan horse as it means that incumbents like Lazada and Mercadolibre ignore Shopee due to its perceived focus on cheap goods and are happy to let Shopee thrive in that end of the market. Slowly however, as Shopee increases its trust and stickiness with its users and introduces higher value assortment, they gradually start encroaching on higher priced categories that are traditionally dominated by these incumbents. This is why now we see Shopee outcompeting Lazada in many of Lazada’s traditionally strong categories such as electronics (discussed more later on).

Leverage 3P logistics partners, and provide free shipping to accelerate the flywheel

Logistics has always been a problem for Southeast Asia due to the relatively complex landscape structure (fragmented multimodal transportation, multiple islands etc). As a young e-commerce company Shopee’s strategy has been to rely on local third party (3P) logistic partners. Its two main partners are the two biggest Indonesian delivery companies, J&T and JNE. As Shopee scaled up, J&T and JNE scaled up with it, reducing logistics costs in the process (greater network density, optimised routes and orders per trip). This further benefits Shopee and its customers.

“A J&T employee in Indonesia told LatePost that the density of J&T’s outlets in Greater Jakarta increased from a handful in 2018 to “one per 5 km.” In order to move more goods to Indonesia, a country that consists of more than 1,000 islands, J&T also purchased a number of cargo ships. Reportedly, by mid-2018, most products purchased on Shopee could be delivered within three days, with some even arriving the next day.”

Lin Lingyi (from KrAsia article “Here’s how Lazada lost its lead to Shopee in Southeast Asia” )

Interestingly J&T is now expanding into LATAM, where Shopee already operates and no doubt looking for a reliable logistics partner who understands them well. Similarly, as well pointed out by James Booth, J&T’s expansion plans into MENA could also be indicative of a future market for Shopee:

Shopee has also started building out its own express delivery services (Shopee Express). At this point, this is largely restricted to trucking fleets in metro/tier 1 cities within its ASEAN markets, and is largely complementary support to the 3PL services. Its main focus is to manage peak season or unprecedented situations such as lockdowns, when there could be a constraint in capacity. Also, given Shopee is now managing a number of global markets, quite likely they may be putting some of their dry powder to purchasing aircraft.

To further accelerate the flywheel, Shopee offers free shipping and other discounts to attract customer traffic, which in turn attracts more sellers, and so on and so forth. This along with the initial zero commissions for local C2C merchants is obviously an expensive strategy but Sea is in a unique position to be able to fund this due to the significant cash flow generated by Garena. Superficially this can be seen as an unsustainable strategy as it’s essentially ‘buying revenue’. However the main objective of the free shipping is to attract new customers to the store. Once they are there, it is up to platform’s value proposition (product range, experience, delivery times etc) to turn them into a loyal customer, not so much the continued free shipping/other discounts. As a heavy user of Shopee I’ve noticed that over time free shipping has become rarer, a sign of Shopee pulling back the incentives (at least for existing customers) now that they have aggregated the scale.

One more noteworthy point on distribution is that in Taiwan Shopee has been implementing O2O (online-to-offline, offline-to-online), and have been rolling out a network of physical stores. At the moment there are approximately 60 stores and they not only act as delivery pickup points, but you can actually also buy simple goods from there like snacks and basic food items3. It’s interesting to see Shopee experiment with omni-channel like this, and through some channel checks that I made I’m very confident that Shopee is looking at similar investments in offline retail in other markets.

Aggressive and creative marketing strategies through influencers and monthly promotions

Shopee was amongst the first to initiate brand ambassadors that appeal to each market. It uses both huge global celebrities as well as local influencers to promote its brand, particularly ones who appeal to the younger demographic who tends to be the target demographic for Shopee. It first hired Kpop superstar group Black Pink as a brand ambassador in 2018, followed by football legend Cristiano Ronaldo, and most recently Jackie Chan. Local celebrities include Bam Bam (famous Thai rapper and singer) for Thailand, and comedians Mark Lee and Phua Chu Kang in Singapore. Lazada has traditionally relied on old form of marketing which involves paid advertisements on Facebook and Google, although it too has followed Shopee in signing up celebrity brand ambassadors.

Shopee’s advertising campaigns tend to be more creative, humorous, and skew to the younger crowd. Its ads have become known for catchy songs and ridiculous dance routines which do not take themselves too seriously. Also when they do outdoor advertising, there are often no expenses spared, with whole stations and trains sometimes covered in ads.

The last key part of their marketing strategy is monthly sales events such as 1.1, 2.2, 3.3,…, 11.11 and 12.12. These events usually generate large sales for Shopee. A large part of that is due to aggressive discounts and promotions that Shopee offers during this period. Again, Lazada has similarly copied this strategy whereby now the two go head to head every month with these events.

Focus on customer experience, and increase user engagement through gamification and social commerce

For Shopee, generating a superior customer experience is most critical, as they understand that if you lose the customers you will lose the merchants, and the whole platform can unwind. This manifests itself in a number of ways. From being one of the first apps to implement chat functionality with merchants, to Shopee’s no-fuss returns policy, to implementing “Shopee Guarantee” which protects customers by withholding payment to the seller until the buyer confirms the receipt of their order, Shopee prioritizes customer trust and satisfaction, often at the expense of the merchants.

Shopee has been highly focused on maximising user engagement and time spent on the app through several features which make the shopping experience more fun. The more users come back to the app, the more likely they are to find something to buy. I understand that daily average visits and time spent in the app are very important internal KPIs that get significant attention from Chris Feng, and middle management is under serious pressure to ensure these do not start slipping.

Once again leveraging its Garena experience, Shopee introduced a rotating roster of games which allow users to win rewards (Shopee Coins) which can be used to make purchases. During its most recent 9.9 sale, Shopee Shake was played 440m times. It also encourages buyers to show off or post about their purchases to earn rewards. The Shopee Feed is a continuous-scroll of multimedia listings of products that allow buyers to follow their favourite sellers and to like or comment on product listings. In 2019 it introduced Shopee Live, a feature where sellers livestream themselves to promote products or interact with buyers, with integrated transaction functionality. This is very much a copy of the social commerce live streaming which has been pioneered by Alababa’s Tmall and become hugely become hugely popular in China. This is clearly is becoming popular in Southeast Asia as well with Shopee reporting 24m hours of Shopee Live being watched during its latest 9.9 sale. All of these features have been highly effective in increasing user engagement with Shopee ranking first in total time spent in app on Android in Southeast Asia and Taiwan in Q2’21.

It will be particularly interesting to watch how this whole social commerce trend plays out. Social media giants like TikTok and Facebook are making big moves in the space given it is a natural extension of their business, and companies like Shopify are helping them enable it. Shopee will have to stay vigilant and execute well to make sure they don’t get left behind.

COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE - LAZADA, TOKOPEDIA-GOJEK, MERCADOLIBRE

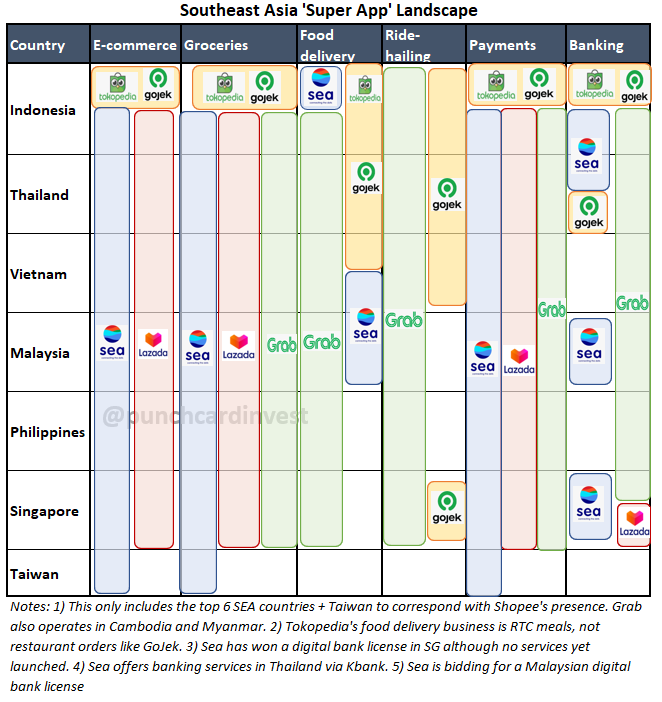

While all of the Southeast Asian internet giants started off in one core business (e-commerce for Shopee, Lazada and Tokopedia; ride-hailing for Grab and GoJek), they have all expanded into adjacent services in an effort to evolve into super apps. The term super app refers to a closed ecosystem of many apps/services that consumers would use regularly. The super app model was originally pioneered by Tencent’s WeChat, however, soon became adopted by most Asian internet giants as they tried to win increasing share of the growing internet economy in these countries and leverage the synergy benefits from seamless integration of services. The below chart maps out the ever-evolving landscape and highlights the increasing overlap between the services offered by the major tech players, from e-commerce to ride-hailing to fintech. This landscape is dynamic, and it is certainly possible that the ride-hailing giants like Grab may use their dominant position in delivery to enter e-commerce and cross-sell to their captive audience, effectively acquiring their customers for zero CAC.

Focusing specifically on e-commerce, each country has several players competing intensely for market share. With each country being its own distinct market, the competition and therefore the network effects are highly localised. The largest markets in the region - Indonesia in Southeast Asia, Brazil in LATAM - have seen the emergence of strong local players - Tokopedia and Bukalapak in Indonesia, Magazine Luiza and B2W in Brazil. Excluding these local players, the other countries in the region are captured by large regional players - Shopee and Lazada in Southeast Asia Mercadolibre in LATAM. An important difference in the competitive dynamics is that unlike in Southeast Asia, in LATAM there isn’t a clear strong number 2 regional player, which presents an opportunity for Shopee to take that position.

The two biggest competitors to Shopee in Southeast Asia are Lazada and Tokopedia. Lazada was founded by Rocket Internet in 2012 and was acquired by Alibaba in 2016 in a series of investments. It plays in all of the major Southeast Asia markets like Shopee (except Taiwan) and for a long time it had enjoyed an advantage as the first-mover and the largest player in each market, until Shopee surpassed it in 2017. Tokopedia is the incumbent Indonesian e-commerce player who started operations in 2009 as an e-commerce platform and has since then added a multitude of other services. It is the second largest unicorn in Indonesia after ride-hailing giant GoJek, and has received over $2.8bn in funding, including a major investment from Alibaba. Most notably, in Feb-2021 it announced that it was entering a merger with Gojek to create GoTo. While Shopee, Lazada and Tokopedia may appear somewhat similar on the surface, they all have slightly different positioning, strengths and weaknesses. Below is a summary of the key differences.

Based on some research conducted by Momentum Works in the Indonesian market, as can be seen below generally all of the players are well regarded along the key criteria on which consumers evaluate e-commerce platforms (product selection, delivery times, mobile app quality, and savings/price). However, Shopee does edge out the competition particularly on product selection and savings - not surprising because as discussed earlier these are critical points of differentiation in Shopee’s approach.

The apps of the different platforms are increasingly looking quite similar, with similar features and design, particularly with their increasing use of engagement tools and social elements (games, livestreaming etc). In a way this could be seen as a reaffirmation of the success of Shopee’s platform design given they were the first to implement a lot of these features in Southeast Asia (which they in turn adopted from Chinese players like Alibaba). But it also highlights how important execution is in this business, as they need to continuously innovate and experiment with new features just to keep slightly ahead of the competition who can easily copy most elements of app design. The similar ratings that Shopee, Lazada, and Tokopedia apps have on Apple App store and Google Play further reinforces how close the user perception of the platforms is.

Lazada: How First-Mover Advantages Can be Lost

Lazada is an interesting case study of how being a first-mover does not necessarily lead to a sustainable leading position. Lazada was established as predominantly a 1P inventory carrying retail model instead of a 3P marketplace. Its focus on standardised categories such as consumer electronics and building out of its own logistics (warehouses, delivery and payments) made it extremely cost efficient in those categories, at the expense of having a differentiated marketplace with lots of repeat purchases. Lazada however helped to promote the awareness of e-commerce through its aggressive advertising campaigns, and there was still the opportunity to leverage its position as a first-mover and expand into a broader marketplace. However, internal cultural issues together with integration mismanagement with Alibaba (who began to acquire Lazada in 2016) meant that the company’s efforts would be derailed for some time. Under Alibaba, Lazada went through three CEO changes in two years as well multiple changes of country heads. There were sweeping personnel changes throughout with hundreds of Alibaba’s middle management employees being assigned to various positions within Lazada. However because of their lack of understanding of unique local conditions as well the imposition of a very Chinese culture, staff attrition spiked, with a large number of people jumping ship to Shopee. Alibaba also forced Lazada to switch to its technology back-end (the same back-end that powers Taobao), however the pace with which this was done and the complexity of the new platform led to significant problems which alienated merchants and disrupted operations.

All of these problems gave Shopee the opportunity to capitalise on Lazada’s stagnation. Chris Feng, who came from Lazada and was acutely aware of its problems, launched an offensive by trying to win Chinese wholesalers onto Shopee and rapidly built scale through offering of low-priced differentiated goods, which was what Southeast Asian market consumers were after. While Lazada continuously struggled to adapt to local markets first under its European owners Rocket Internet and then under Alibaba, Chris Feng built up big local teams in each market and spent 80% of his time each year in Indonesia, even picking up the local language. With many of the Shopee management team having come from Lazada, they carried over their expertise in logistics which were then successfully implemented at Shopee. It’s not hard to see why within a few years Shopee overtook Lazada in every market.

However, Lazada should not be dismissed as a competitor. Alibaba veteran Li Chun who has been heading up the business for a number of years (although he only officially got promoted to CEO in Jun-2020) seems to have restored a bit of stability to the platform. He is recognised as an experienced executor who is humble and dedicated, and has been working on restoring Lazada’s relationships with its merchants and customers. Backed by Alibaba’s capital and a renewed focus on the region (especially given the domestic political and regulatory situation in China), Lazada under Li Chun has been employing similar tactics to Shopee. In Singapore you can’t escape the advertising wars between Shopee and Lazada, and the battle of ambassadors/influencers, from Jackie Chan to Korean artists. Lazada has similarly employed free shipping and store discounts and been significantly widening its merchant base to increase the product range in its marketplace. Lazada is trying to undo mistakes of the past and continually making it easier for merchants to sign up to their platform, like recently introducing a new simple three-step seller registration.

There are clear examples of Lazada leveraging its Alibaba relationship successfully. For instance, you can now buy things from the Taobao platform on Lazada. This allows Lazada users to access Alibaba’s Chinese Taobao merchants directly with over 100m products. However, a quick scan of a few the Taobao products also found them on Shopee as well. Essentially what this shows is that most merchants would list on both Lazada and Shopee given they are the dominant pan-Southeast Asia players.

In short, Li Chun’s leadership seems to be bearing fruit, with Lazada seeing growth of over 90% in Q2’21 in its orders according to Alibaba’s earnings report (although this is still lower than Shopee’s 127% order growth for the same period). According to Lazada, over the first six months of 2021 they saw new seller sign-ups increase over two times across Southeast Asia, compared to the year before.

Interestingly Lazada seems to have a greater product listing across all categories that I searched, even ones where Shopee is perceived to be stronger such as fashion and accessories. This highlights how as e-commerce platforms build up scale the product listing advantage that one platform may have over another essentially shrinks. It really becomes more about the association that consumers have of a certain platform with specific categories.

With a lot of the same merchants on both platforms, it is instructive to see how the followers and engagement for the same stores compare across the two platforms. Below is a comparison of some well-known stores across various categories. Generally, for most stores, there were more followers on Shopee, and the number of reviews was consistently higher on Shopee by miles. This was even the case for electronics, a category which Lazada was traditionally strongest in. This highlights to to me not only the higher MAUs for Shopee but also the much higher engagement. Again, this is a strong reflection of how focusing on a superior consumer experience has provided Shopee with an edge over similar looking competitors.

Tokopedia-Gojek: The Indonesian Incumbent Super-App

In the battle of regional super apps, few will be bigger than the merged entity Tokopedia-Gojek (together GoTo). Tokopedia’s core business is a B2C/C2C marketplace which has over 9.7m merchants on its platform and attracts over 3m DAUs. While Tokopedia started as a marketplace, it soon bolted on over 20 other digital services including grocery delivery (TokoMart), food delivery, online pharmacy, travel and ticket bookings, and a whole suite of financial services such as payments, lending, investments, tax, and insurance. For its e-wallet, it has a strategic investment in OVO, a leading Indonesian mobile wallet, of which it owns 41% ownership, with Grab being the other major shareholder. Other services are offered through collaborations, for instance the travel service is a partnership with large Indonesian OTA Traveloka. In comparison, Shopee only last year launched its food delivery business in Indonesia (ShopeeFood) and a grocery business (Shopee Segar). Thus Tokopedia has a significantly greater offering than Shopee.

Up until 2017, the Indonesian e-commerce market was dominated by Tokopedia, Lazada and Bukalapak as the top 3 players. That all changed when Shopee launched and quickly built up scale via its value offerings, free deliveries and promotional activities. In 2020 Shopee overtook Tokopedia in terms of MAUs, and depending on which metrics you look at Shopee is now either number 1 or number 2 in Indonesia. Nonetheless the race between them is tight.

With Tokopedia’s merger with GoJek, the combined GoTo business is expected to be worth ~$18bn, and will be the first regional internet giant to combine e-commerce, ride-hailing/on-demand services, and fintech.

GoJek is the leading Indonesian ride-hailing platform which also operates in Vietnam, Thailand and Singapore, with over 2.5m daily active users (over 50% are in Indonesia). It is estimated that across Southeast Asia it has 25% market share of the ride-hailing market, with market leader Grab owning about 70%. Although it began as a ride-hailing app, it soon evolved into a super app with services such as package delivery, food delivery, groceries, news and entertainment, and payments.

The potential benefits of combining the Tokopedia and GoJek ecosystems are large, making them a stronger competitor to Shopee. Firstly, there are logistics synergies from Tokopedia being able to leverage GoJek’s fleet for last-mile delivery (they have not been investing in their own). There are also complementary benefits from combining each of their groceries and food delivery businesses given they have slightly different focuses, strengthening their product offerings. Also the combination of data that both businesses have will produce the largest databank on Indonesian consumers of any internet company. This should put them in a formidable position when it comes launching new products or services.

Finally, GoTo will likely publicly list in 2022 in Indonesia, followed by the US, giving it access public market capital to fund its growth like Sea. Previously Sea was the only real way for investors to get a pure-play public market exposure to the fast-growing Southeast Asian, however now with a listed Grab and GoTo, competition for capital will become more tight (hence likely why Sea chose to strategically raise $6.5bn in equity and debt capital this year in anticipation of this - its biggest raise to date).

Of course merger integrations, particularly of this size, are highly complex and costly. The integration of competing technology stacks, products/features and company cultures will take considerable time and may be disruptive to the business. Shopee needs to keep focused during this period to entrench its position, as the potential threat of the enlarged GoTo entity is not to be taken lightly.

MercadoLibre: The Amazon of LATAM

Unlike in Southeast Asia where the market is dominated by a handful of players, the LATAM market is pretty fragmented. MercadoLibre (MELI) is the dominant regional player, operating in 18 countries and with approximately 30% market share. However after MELI there isn’t a clear second player, with a number of strong local players but no major regional player. Shopee is currently operating in four markets (Brazil, Mexico, Chile and Colombia), and reportedly exploring expansion into Argentina and others.

Both MELI and Shopee are 3P marketplaces focusing on the C2C/B2C model. However, they are not in head-on competition (at least not yet) due to their different positioning. Shopee is employing a similar strategy in LATAM as it has in Southeast Asia, where it initially focused on bringing a long-tail of low-priced categories such as fashion and apparel from international (predominantly Chinese and Korean) sellers. This contrasts with MELI which began with a focus on more traditional categories that went online first such as consumer electronics. The MELI website for instance is very heavy on smartphones, computers and peripherals, which are all fairly large ticket items that have low purchasing frequency. The difference in category mix reflects in the AOV where MELI's AOV is >3x of that of Shopee. So while Shopee might be winning in app downloads and MAU, this would not be reflective of the real market share differences between the two.

The other key difference is that MELI has been investing heavily in logistics. MELI has an unbeatable delivery system built from scratch that doesn’t rely on state own postal services. Shopee will be relying on its usual 3P strategy of using local shipping companies (they have also been reportedly encouraging their trusted ASEAN partner J&T to enter the LATAM market). It will be significantly behind MELI in this area for some time and management has indicated that LATAM logistics are more expensive than Southeast Asia, so I expect significant cash burn and unprofitable unit economics for a few years or so while logistics costs come down. MELI’s fulfilment times are typically 1-2 days which contrasts with Shopee c. 4-11 days (which might in part be due to the cross border nature of goods).

Clearly Shopee will not be able to displace Mercadolibre in the region, however there is a non-zero chance that it can become the number 2 regional player. So far it is off to a good start with the app becoming the most downloaded e-commerce app in the region according to AppAnnie despite it only being four countries so far.

AN ASSESSMENT OF SHOPEE’S MOAT

It is quite clear that Shopee is competing against some large players who are capable of providing a similarly large product range, app features, and functionality. They also don’t necessarily lack the capital to invest aggressively. Shopee came out of nowhere and within a few years surpassed the others, in large part through heavy cash burn on discounts, free shipping and advertising campaigns. So what’s stopping another well-funded player from doing the same and stealing Shopee’s market share? Does it actually have a sustainable moat (beyond the significant capital inflows from its Garena cash engine and the public markets)?

Generally, e-commerce evolves towards an industry structure with 1-2 large platforms dominating the market. In a lot of the major markets the first-mover incumbent has generally taken the lion’s share, with a big gap between them and the next largest (Alibaba in China, Amazon in US, MercadoLibre in LATAM). This is a natural byproduct of the laws of scale and network effects that platform businesses like marketplaces exhibit. Merchants will naturally gravitate to the platform that has aggregated the most buyers, and buyers in turn are drawn to the platform with a larger variety of offerings. As market share consolidates behind the top 1-2 players, pricing power follows. Platforms can increase commissions, ad inventory becomes more valuable due to a higher audience, and other value-added services get more sophisticated and adopted over time.

As laid out in the earlier sections, Shopee’s heavy cash burn on customer discounts, free shipping, no commissions and marketing is part of a tightly integrated strategy that requires significant execution capability to pull off successfully. This has led it to a market leading position across the region - Shopee is the clear number 1 in each ASEAN market, except in Indonesia where it is closely tied with Tokopedia. This has allowed it to exhibit pricing power, evident in its it raising of commissions and overall take rates across most markets over the last year (more on this later). Similarly, the value-added services such as advertising have now started ramping up as well. This is a strong sign that it is establishing a moat in the form of scale and network effects. How durable this moat is however only time will tell.

The reality I think is that Shopee will always exist in a heavily competitive environment and be vulnerable to market share losses to existing players or upstarts. For instance we saw Tokopedia pass Shopee as the most visited site in Indonesia in Q2’21, largely driven by aggressive discounting. However there is some nuance to this. The categories which Shopee skews towards - fashion, health and beauty, are lower priced categories which are bought with high frequency, and with these people generally tend to be less price sensitive and do less price comparison. Lazada in comparison has over 50% of its GMV coming from electronics, which are bigger ticket items bought a lot less frequently and tend to be priced compared significantly, meaning the customer needs to be ‘re-won’ each time. Longer term, as scale emerges, it is harder to differentiate on categories (as mentioned Lazada for instance now has more product listings than Shopee across all categories including fashion). Nonetheless some e-commerce companies get associated with specific categories which may help them sustain a larger share in those segments, like Shopee seems to have with fashion and accessories, and Lazada in electronics. This does bestow Shopee with some advantage around customer stickiness and should allow them to pare back discounts and free shipping (which they have been doing).

The other key point is that even if Shopee loses some markets (eg. becomes number 2 in Indonesia) while not ideal, this wouldn’t kill the business. Shopee operates independently on a country-by-country basis, which means that on a portfolio level it can survive the loss of one market if others are still doing well.

Nonetheless given the competitive intensity, this is not an industry where management can afford major slip ups in execution (Lazada case in point). Shopee will face a constant pressure to keep innovating and executing on product, service quality, user experience as well as pricing to stay ahead of the competition.

THE MARKET OPPORTUNITY

Shopee is exposed to high growth emerging markets which are still very early in their e-commerce penetration (~6%) vs. world average of 10%, meaning significant room to scale up. Increasing online habits, increasing assortment of products, and reducing logistics costs, should all help underpin that growth. E-commerce penetration in LATAM is even earlier than Southeast Asia, so Shopee entered an early period while the market still have significant room to grow.

Shopee operates in 11 markets, which have an approximate e-commerce TAM of ~$170bn. The interesting thing is that by entering LATAM, Shopee has effectively doubled its TAM. The below table from Momentum Works is a great side-by-side summary of Southeast Asia and LATAM markets, showing how roughly similar they are in terms of population size and GDP. Interestingly, Sea views LATAM to actually be a lot more homogenous as a region in culture, consumption preferences and income levels across the countries compared to Southeast Asia. The learning lessons from ramping up in Southeast Asia would stand the company well in terms of fine tuning LATAM country strategies.

The below chart shows the projections of e-commerce GMV for ASEAN+Taiwan and LATAM-6 markets. Both are expected to grow at CAGR of c. 20% until 2025, and longer term the expectations are for the TAM to approximately 4x. This is being driven by continued increase in e-commerce penetration rates and rising incomes of these emerging markets. Even though it may seem like Shopee was late to entering LATAM, it is clear that in the context of the next decade this is still quite early.

Of course with Shopee’s recent expansion into India and Eastern Europe, the TAM has been increased even further (perhaps something to cover in the future).

PATHWAY TO PROFITABILITY

Probably the biggest concern that investors have with Shopee is when and if it can reach profitability. The below chart really highlights this issue - as revenue has grown, EBITDA losses have grown with it.

A common criticism of Shopee is that it has been ‘buying market share’ through significant discounts and free shipping, is reliant on expensive advertising campaigns with big celebrities, and constantly expanding into new markets which is continuously pushing out their breakeven point. Any tech investor would understand the importance of building scale as a moat for internet businesses, and this often means many years of unprofitability and cash burn before the businesses can become profitable in a more mature future state. However to determine whether this is feasible it’s important to understand if the business is establishing profitable unit economics, which should then technically allow it to reach profitability as the company scales. The data that Sea often points to is the reducing loss per order - as the business scales, it should be able to increase pricing power (higher take rates), become more efficient with its logistics costs, and have greater operating leverage on its overheads. This has clearly been the case, as we can see below:

This is not a completely accurate depiction of unit economics as it represents profitability at a segment level rather than individual customers; it captures full overheads related to the business including fully loaded marketing costs (both brand and direct response marketing) and R&D. The company does not disclose any more granular information. This is okay though as ultimately profitability at the segment level is what we are most focused on.

The key driver of profitability will be the improvements in take rate. As Shopee has become the dominant e-commerce platform in Southeast Asia, it has generated significant value for its merchants and the ecosystem, which means they can exhibit pricing power by raising commissions. The merchants are happy to pay these as Shopee is an increasingly important channel for them. The clear relationship between growing GMV and take rates is shown below:

As the business has scaled, it has also been achieving operating leverage on its sales and marketing, which has been reducing significantly both as an aggregate % of revenue and on a per order basis. A large part of that is due to the semi-fixed nature of things like brand advertising. Over time however Shopee has been able to reduce the amount of discounts they offer to customers as people have been somewhat ingrained with the idea that Shopee has the ‘best prices’ for everything. For instance I have noticed that in the past they used to frequently give out 25-30% off vouchers, now they are mostly now 5-10% off.

Management claims that Shopee has been EBITDA positive in Taiwan for a while and has just reached profitability in Malaysia, where as showed earlier they have achieved a dominant position. So the trajectory looks positive, however to determine whether the whole business can reach profitability it is important to dive into its key driver, the take rate, as there is quite a bit of nuance to it which has important implications for profitability.

Take-rates

The take-rate is one of the most important metrics that investors of e-commerce businesses focus on as it represents how much of the GMV that passes through the platform gets converted to revenue. Below is a comparison of Shopee’s take rates to other global marketplace peers. It is already higher than the Chinese e-commerce peers (Alibaba, JD, Pinduoduo) although clearly still some way lower than MELI and other LATAM/developed market peers. I note that comparing take-rates across companies and markets is somewhat fraught with danger due to the different composition and market dynamics, although it still provides a helpful perspective.

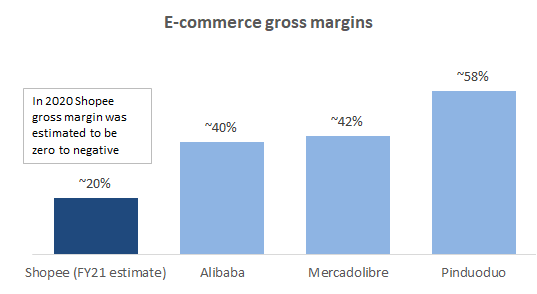

Despite Shopee having higher take rates than its Chinese pure marketplace peers, it has significantly lower gross margins than both of them - estimated to be ~20% in FY21 (it was negative in FY20 and earlier), vs 40-60% for the peers. The reason for this is due to the composition/drivers of the take rate.

The take rate typically comprises of several components 1) commissions and service fees, 2) advertising, 3) payment fees, and 4) logistics. The composition of the take rate has important implications on profitability of the marketplace.

Currently ~80% of SE's take rate comes from logistics and payments. They are low/zero margin revenues as they have an associated cost in your cost of sales that almost completely nets out the revenue. Logistics revenue received is basically paid out almost entirely as a cost to fulfill the orders (and Shopee would often subsidise these with free shipping). Similarly, with payments, there is a corresponding cost to the banks/credit cards in order to settle the transaction, with very little net margin going to the platform. In contrast commissions and advertising have very low marginal costs - hence they are very accretive to margins.

As described earlier, when first entering a market Shopee starts off with zero commission rates to C2C sellers and generally low commission rates on other segments (B2C and Shopee Mall) as a way of building scale. This means that the commission component of the take rate in prior years has been low. However, all signs are pointing to increasing commissions components over time. Shopee has recently been raising commissions across most of the markets:

Similarly, advertising and other value-added services are also very low when the platform is in the early stages of scaling up. The below chart shows how low advertising components are for Shopee vs. the peers and how early it is in its advertising journey.

For the last few quarters, management has been consistently saying how advertising is increasing as sellers are getting educated on these services.

In terms of the monetization contribution by ranking, so our -- as you know, most of our monetization came from the high-margin types of revenue, i.e., transaction-based fees, including commissions and various types of handling fees, et cetera, as well as advertisements. And more importantly, the increase in the take rate we're seeing quarter-on-quarter is attributable to these types. And in particular, for second quarter, attributable to advertisements adoption and mainly from increasing adoption, including number of sellers placing advertisements on our platform.

But still very early stage for us. I think our advertisement take rate is still low, and we have much more inventory to be rolled out and to be adopted. As we explained before, we believe our markets are still at early stage for the e-commerce ecosystem, and it takes time for our seller community to be trained and get familiar with various types of advertising and marketing tools we can leverage on our platform, and we focus on educating our seller communities on that.

Yanjun Wang, COO, Q2’21 Earnings call

Assuming advertising can reach 15% of the take-rate by FY25, that would be approximately a $1.5bn revenue item just on its own.

So the key point is that it’s not just growing take rate that matters, it’s the components of the take rate that are also important. As the high margin components of commissions and advertising increases, gross margins should increase accordingly and should be able to reach 40-50% by FY25 in line with the peers (there is already an expected increase from ~0% in FY20 to ~20% in FY21 just off slight gains in commissions and advertising). With further operating leverage on sales and marketing, this should allow for a 15-20% EBITDA margin in a steady state.

There is another key point to make on monetisation - Shopee is the key driver of the SeaMoney business as it facilitates the cross-sell of financial services such as BNPL and lending to sellers and buyers. Shopee and SeaMoney are intrinsically and synergistically linked, something I will explore further in my next deep dive.

FORECASTS AND VALUATION

Forecasts - Base, Bull and Bear Cases

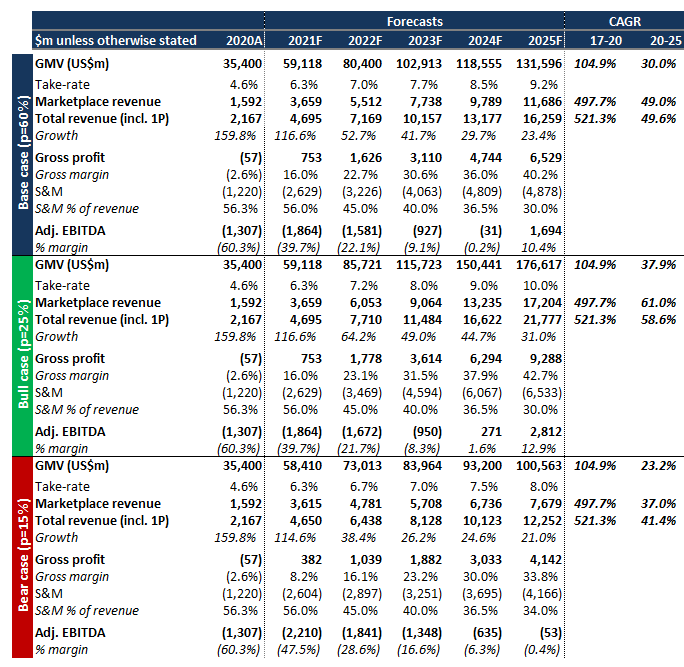

Given the wide range of potential outcomes for a high-growth business like Shopee, I have run a range of scenarios with base, bull and bear cases, which I then combine in a probability-weighted valuation. As a reminder, I forecast out to FY25 to be able to calculate a range of IRRs over such a hold period and get a rough sense of risk-reward asymmetry.

The key drivers of Shopee’s revenues are GMV, and take-rates. Working top-down from the TAM for each market, and assuming a range of market shares, we can calculate the forecast GMV for Shopee. My assumptions and build-up for what Shopee’s GMV could look like in FY25 is laid out below:

Generally, I have assumed that in the base case Shopee maintains its dominant (~50%) market share in ASEAN e-commerce, is able to win 10% market share in ASEAN food delivery, and is able to carve a out 20% share of the Brazil market and 5% of the rest of the LATAM. There are also now a number of other markets that Shopee has entered (India, Poland), plus likely others to come over the next few years. For now, I will not be building these up at a granular level given how nascent these expansions are, and have just conservatively estimated $5bn from the rest of the world in the base case. Under this scenario, FY25 GMV is $132bn, representing a 30% CAGR from 2020 levels. In the bull case I have assumed Shopee can win even higher market share, particularly in LATAM where there is significantly more upside for them, plus a greater contribution from the rest of the world. This results in a much higher GMV of $177bn (38% CAGR from 2020 levels). Conversely with the bear case I have assumed they lose market share loss in their core ASEAN markets due to more aggressive competition, and limited success in LATAM and rest of the world, resulting in a GMV of $101bn (23% CAGR from 2020 level).

In terms of take-rate, I have assumed that it will rise from ~6% in FY21 to 9% by FY25 in the base case, driven by continuation of increased commissions and advertising, as well as a higher contribution from LATAM which has much higher take rates (12%) compared to other regions (0-6% for Southeast Asia).

As discussed earlier, I expect that the mix shift towards higher margin revenue components (commissions and advertising) as well as continued reductions in logistics costs due to scale and efficiency, should help Shopee achieve ~40% gross margins by FY25, in line with its peers (in the bear case I assume that level is not reached due to lower monetisation).

I have also forecast continued operating leverage on S&M, which reduces from ~50% of revenue today to 30% of revenue by FY25 (Alibaba is around 12-16%, Pinduoduo is currently at ~50% but expected to reduce to 30% longer term, Mercadolibre is at ~22%). Part of this reduction is due to the semi-fixed nature of brand advertising, but also as mentioned Shopee should be able to start paring back customer discounts as they scale and build loyalty, and they have already started doing this.

The below table summarises the key output from each of the scenarios:

Overall, the above scenarios results in the following FY25 outcomes:

Total revenue in the range of $12.3bn to $21.8bn (vs. $2.2bn FY20)

Adj. EBITDA in the range of $0bn to $2.8bn (vs. -$1.3bn in FY20)

The one thing that is clear is that I don’t expect Shopee to reach EBITDA profitability until FY25. With its strategy of continuous investment in S&M and global expansion, I think it’s reasonable to assume that management is prioritising growth at the expense of profitability, and I expect they would have no issue pushing out the breakeven point as far as possible.

Valuation

Given that Shopee is not profitable, the business is generally valued on revenue multiples. Looking at the 5-year average rolling NTM Revenue multiples of key fast-growth emerging market e-commerce comps such as Mercadolibre and Pinduoduo, a revenue multiple of 10x appears reasonable for valuing Shopee in the base case. The bear case I have pegged at 8x and the bull case at 12x to account for the slower/faster growth respectively in these scenarios. The resulting probability-weighted valuation is below:

In the base case I am deriving a valuation of ~$136bn if discounted to today , or $209 p/share. However we can see that the range is pretty wide; between $81bn ($125 p/s) to $221bn ($341 p/s). The bottom end (bear case) might look pretty dire, however just to emphasise that this is a scenario which captures the risk of Shopee losing market share in its core markets and having very limited success in LATAM/rest of the world. Based on management’s consistent track record of outperformance to date I would think that my bull case is more likely than the bear case. Thus I’ve assigned a slightly higher probability weight to the bull case than the bear case (bull case p = 25%, base case p = 60%, bear case p = 15%). Probability-weighting the different scenarios I get a weighted valuation of ~$150bn if discounted to today, or $229 p/share today.

I will go through the valuation of SeaMoney and my final IRR calculations in subsequent articles.

Where I could be wrong

There are number of critical elements to my investment thesis for Shopee which will be important to track over time. If I see signs of impairment to any of these, I may need to question my evaluation:

A central part of my thesis is that customers will show some level of loyalty and stickiness to Shopee as one of the dominant platforms with a wide range of products, competitive pricing, and strong customer experience. This means that they are not using Shopee purely for the highest discounts / free shipping and then jumping ship. If there are indicators that Shopee is losing significant market share due to more aggressive discounting or marketing from other players, then that may indicate that it doesn’t really have a strong differentiation outside of pricing. If that’s the case it will need to be perpetually engaged in a capital war just to maintain its share, which would significantly hinder its long term profitability (unable to pare back discounting/free shipping, marketing etc)

If Shopee keeps burning cash on markets where it is evident that it is unable to succeed or reach profitability after some time. My understanding is that internally the company is conscious of profitability, however if I feel like they are losing their investment discipline, I will be re-evaluating

If overall profit margins are not improving year on year. I am not necessarily looking for a specific breakeven point as I understand that the company is in a significant growth phase, but I would expect to see a positive trajectory over time. If this stops happening then it could be a sign of a depreciating moat and weakening business model

Valuations re-rate downwards. I have tried to address this by looking at long-term average multiples of similar peers like MELI and PDD when determining my range, not just current multiples which may be elevated. However should 10x revenue multiples not be sustained for whatever reason (rising rates etc.), then the valuation of Shopee/SE may be significantly lower

CONCLUSION

A common criticism of Shopee is that it has been ‘buying market share’ and doesn’t have a sustainable business model. The conclusion that I have to come to after spending many hours doing this deep dive is that this is a very superficial view of the business. Its cash burn is part of a highly effective, tightly executed and battle-tested strategy that has been designed to enter a market and build scale incredibly fast in a way that is difficult for competitors to stop. This strategy requires significant execution capability, a crystal-clear vision of Shopee’s value proposition, and an aggressive win-at-any-cost mentality that permeates through the entire business. In turn, the scale and network effects that have been created seem to be establishing a real moat for the business. What follows should be pricing power and a pathway to profitability. Of course execution risk and competition risk cannot be ignored, and I will continue to monitor for any possible impairment to my thesis. Nonetheless Shopee and its talented management team have continued to surpass the market’s expectations and I look forward to following the evolution of this business over time.

If you made it to the end, thank you for reading and hopefully you found the article helpful. I welcome all feedback, good or bad, as it helps me improve and clarifies my thinking. Please leave a comment below or on Twitter (@punchcardinvest).

Also if you’d like to receive Parts 3-4 of my Sea deep dive as they’re published, or future deep dives on other tech companies, please subscribe.

For further reading / info on Shopee:

Momentum Works has really good coverage of Shopee and Southeast Asian e-commerce more generally. I recommend the below reports:

Blooming E-commerce in Indonesia (multi-part series)

Here’s how Lazada lost its lead to Shopee in Southeast Asia (KrAsia)

Shopee’s next big moneymaker? (TechInAsia)

Marketplace Businesses + Shopee (Hayden Capital 2018 presentation at ValueAsia)

Thanks to a Hayden Capital investor letter for this information.

Actual market share data in terms of GMV is hard to come by given the lack of disclosure, so most assessments are based on monthly active users or web visits from public sources.

Liked this! Gives me more conviction to buy

I ran businesses in SEA, especially on Lazada & Shopee and I have to say:

This is pure masterpiece.