I didn’t expect it going into this deep dive, but I think SeaMoney has become the most interesting part of the Sea business for me. The fintech space in Southeast Asia is incredibly dynamic with all of the internet giants, traditional financial institutions and new upstarts making moves. There is a tremendous opportunity for Sea to build out a valuable franchise similar to other global digital payments and financial services players such as Alibaba’s Ant Financial, Tencent’s WeChat Pay, and MercadoLibre’s MercadoPago. This business is one that is evolving rapidly and will no doubt look quite different even a year from now. I look forward to following how it all unfolds.

In this piece I will cover the following:

The market opportunity

Overview of SeaMoney

Competitive landscape

Case study: MercadoPago

Forecasts and valuation

Disclaimer: I am long Sea, and this article is not investment advice nor a substitute for your own due diligence. The objective of this article is to help formalise my thinking on the stock and hopefully provide some interesting insights on the business.

THE MARKET OPPORTUNITY

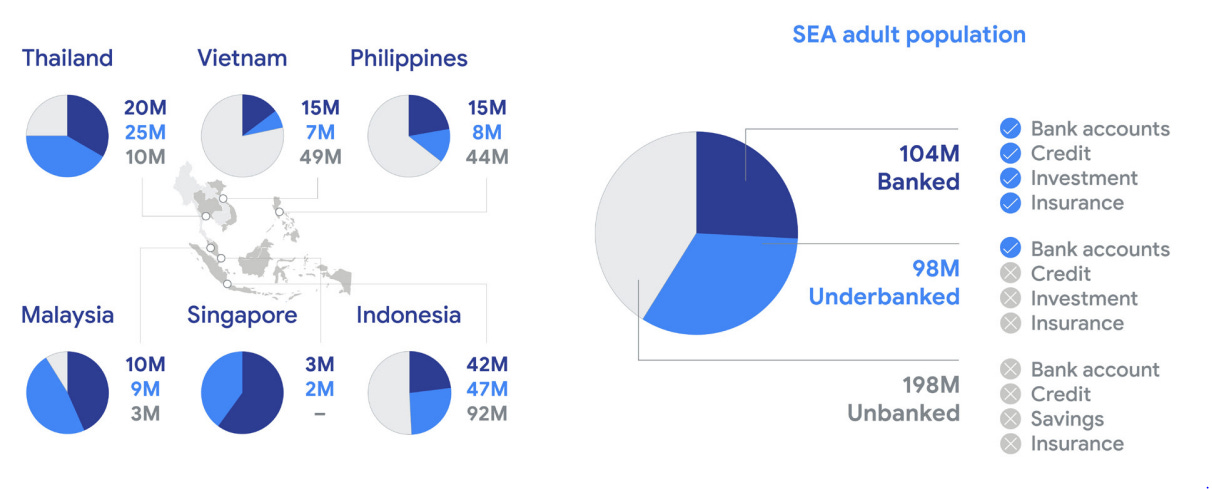

Southeast Asia and emerging markets more broadly are significantly under-penetrated by both cashless payments and financial services. As shown below, about three quarters of the SEA adult population is either unbanked (defined as no access to basic bank accounts) or underbanked (defined as not well served by financial services such as credit cards, insurance, loans etc.). Key reasons for this are usually insufficient banking infrastructure particularly in rural regions and far to reach places (like Indonesia’s 17,000 islands), lack of trust of financial institutions, and in some countries low financial literacy.

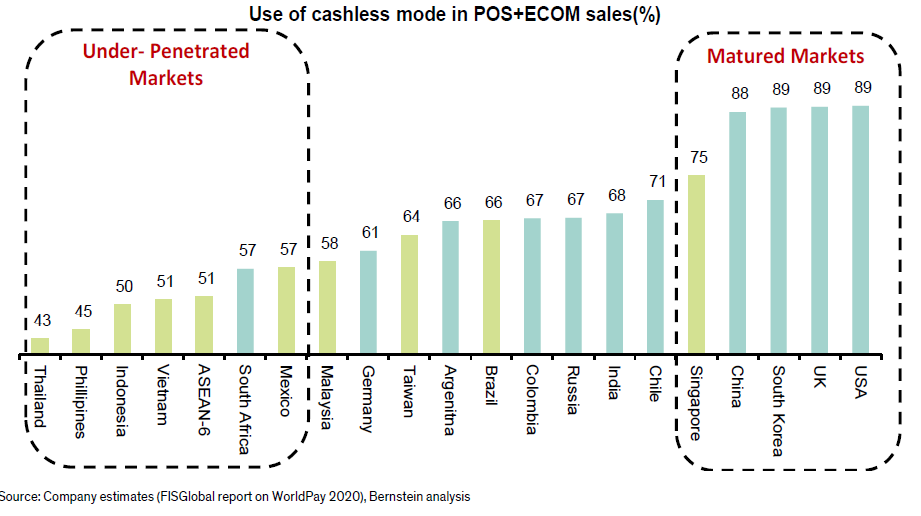

Similarly, these markets have relatively low penetration of digital/cashless payments, such as debit cards or credit cards. Other than Singapore which has ~75% penetration of cashless modes, the rest of the the Southeast Asian countries is roughly at 50%. This is largely due to low merchant adoption of digital payments modes like debit cards and credit cards, as transaction fees of these modes are as high as 3% in some markets.

The under penetration of traditional banking and digital payments is a significant problem as it means a large part of the population is unable to access basic financial services which are essential to building livelihoods and wealth, such as savings and investment accounts, asset management, and loans and mortgages.

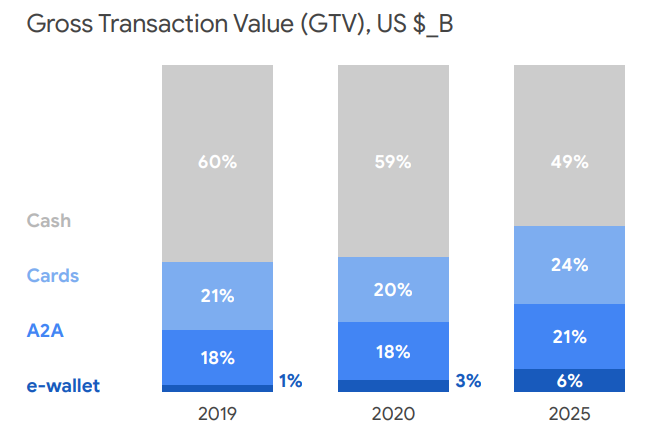

COVID has been a huge factor accelerating the inclusion of the mass public into the digital economy, increasing digital awareness and raising adoption of digital payments. E-wallets and account-to-account payment1 networks has been gaining acceptance in these markets driven by their convenience, low merchant fees and adoption of standard QR codes. Based on Kantar research, the average number of cash transactions by consumers declined from 48% pre-COVID-19 to 37% post-COVID. At the same time, frequency of e-wallets transactions rose from an average of 18% pre-COVID-19 to 25% post-COVID, indicating a massive shift from one payment method to another.

There are ample precedents demonstrating that digitisation of payments can leapfrog payment technologies that have long been established in developed markets, such as credit and debit cards, and head straight to e-wallets/A2A payments. China and parts of LATAM are probably the most relevant examples of this, where owing to the rise of dominant e-commerce platforms, e-wallets rather than credit cards monopolise the market. Concurrently with their strength in online payments, offline merchants are acquired en-masse drawn by the network effects from these large online ecosystems. Close to 100% of MercadoLibre’s e-commerce GMV is transacted via its e-wallet, and it has an even higher share of its payments coming from off-platform payments. Similarly in China big tech companies have over 90% share of payments through the dominant mobile apps AliPay and WeChat Pay.

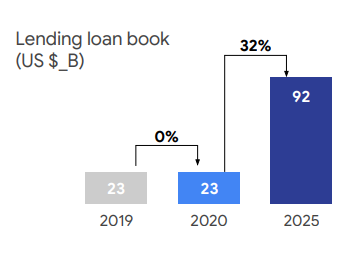

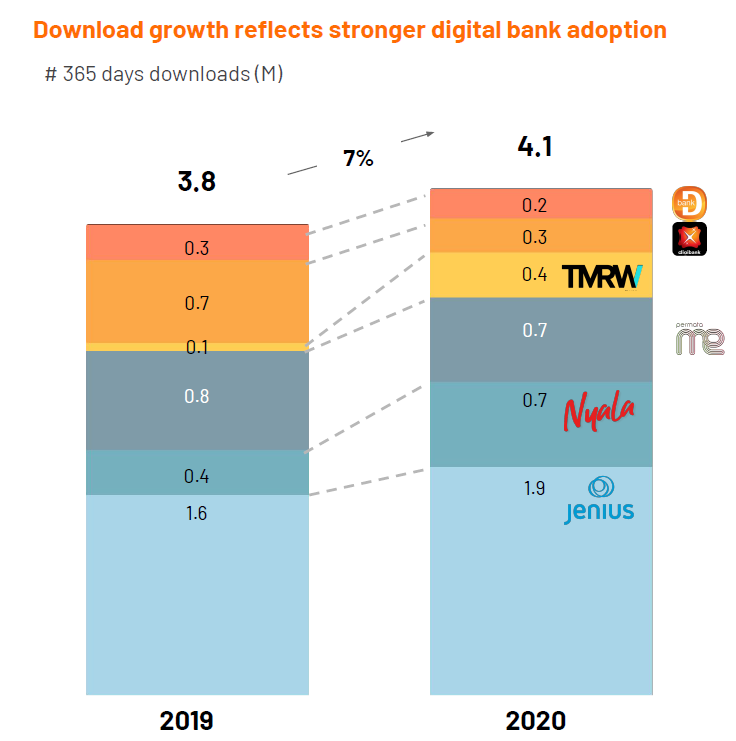

Digital banks have also started to proliferate the landscape. A digital bank is a financial institution that manages the customer lifecycle completely online - from onboarding to withdrawal - whilst having a certain level of security similar to that of a traditional bank. With traditional banks focusing on capturing and retaining higher-income customers with relatively certain high lifetime value, there is huge potential value for anyone who is able to address any part of the large unbanked population in a profitable and sustainable manner. As such, the digital banking opportunity in Southeast Asia is large. According to the Google, Temasek, Bain 2020 SEA e-Conomy report, digital loans in the region are expected to grow to $92bn by 2025, a 32% CAGR from 2020. 2020 was a weak year in digital lending due to COVID-triggered concerns around credit quality and non-performing loans, which saw lender confidence dissipate. However, as the customer base and SME adoption expands, together with digital banks’ improving data/credit risk scoring capabilities, longer-term growth trajectory is very healthy.

The regulatory environment is also increasingly shifting to being supportive of this new digital finance trend and financial inclusion/education more broadly. Singapore has already announced digital bank licenses, which was a hotly contested bidding process with the approvals going to Sea and Grab (in consortium with Singtel). This is a major vote of confidence to the potential fintech services to be offered regionally. Malaysia and Indonesia are also in the process of creating digital banking frameworks, and Thailand is reported to be considering the same. With growing government support and strong secular tailwinds, the major tech players and upstarts are all getting involved.

Why are internet companies getting into fintech and what is their right to win?

The reason large technology companies are attracted to financial services is simple. They have large installed customer bases, powerful brands, access to capital markets and superior data about customer preferences and habits, all of which have the potential to be leveraged into financial services. With more people having smartphones than bank accounts in emerging markets, the tech players are in a unique position to provide these services to people more efficiently and cheaper than traditional financial institutions. In turn, this allows them to build potentially scalable and profitable adjacencies which also have significant ancillary benefits for their core businesses:

Reducing payment friction and increasing the TAM: With poor payment infrastructure in emerging markets, building digital e-wallets helps internet companies facilitate payments on their own services and extend penetration of that service, in effect increasing their addressable market. More broadly, global payments TAM is many times higher than the TAMs of specific sectors like e-commerce or ride-hailing. The more tech companies can penetrate the off-platform economy, the greater the TAM they are opening themselves up to

Increasing user stickiness and lifetime value: The real value in having a scaled payments network is ecosystem lock-in (consumers, merchants becoming reliant on the network) and greater customer attachment to the core platform. Whether it is e-commerce like Shopee or ride-hailing like GoJek, by having money in an accompanying e-wallet, consumers are more likely to keep transacting and spending time on the platform, increasing their lifetime value. In addition, the access to troves of consumer data can be leveraged for cross-selling new financial products and services

Reducing costs: The more transactions can be shifted from third party tools like credit cards to own e-wallets, the less payment processing costs incurred in the provision of that revenue, improving the gross margin. With credit card processing fees in the range of 2-3%, there would be a significant cost savings benefit of bringing payments on to own e-wallets, which would have much lower processing fees. Even a few basis points saving on a $60bn GMV could result in potential savings in the hundreds of millions at the gross profit level

Natural advantage in user data accumulation and more precise targeting: High-frequency touch points like e-commerce and ride-hailing help facilitate significant real-time data collection on consumers and merchants. This provides tech companies with the potential to form an accurate assessment of consumption habits and credit worthiness of a consumer (particularly when paired with other external data), allowing for more accurate and tailored pricing of financial products, whether it’s interest rates on loans or premiums on insurance. In turn the more accurate pricing of risk will allow larger loan volumes to more consumers (some that were previously unbankable by traditional banks) and higher net interest margins.

The end goal of all of these fintech investments is to develop an at-scale, permanent and frequently used payment and financial services layer which generates significant recurring revenue and annuity-like cashflow profile.

BUSINESS OVERVIEW

SeaMoney is the digital finance arm of Sea which houses its e-wallet ecosystems (ShopeePay, AirPay), as well as the newer financial services such as digital banking, wealth management, and insurance. To understand the business today it is important to understand the stages of its evolution from a closed-loop payment tool, to an open-loop payment network, to expansion into other financial services.

Phase 1: Payments and closed-loop/open-loop ecosystems

Most successful digital payments networks start by leveraging their core businesses and providing solutions to existing friction points. AirPay was launched in 2014 as a tool that allowed users to exchange cash for digital currency on their mobiles and used in games on Garena. Many Garena users top up Garena Shells (Garena’s form of digital currency) through cash payments at counters at thousands of local convenience stores across Southeast Asia. With over 200,000 counters across the region, this was a large driver of early e-wallet adoption.

The AirPay app was eventually migrated to ShopeePay in all of Sea’s markets except Vietnam and Thailand where the AirPay brand is strong and well recognised. ShopeePay is the e-wallet that is linked to Shopee and represents the core of the SeaMoney business today. Being able to leverage a core use case like e-commerce was a very efficient way to build adoption on both the consumer and merchant side. Like most digital payment networks, initially it was a closed-loop ecosystem, meaning it was used only for an internal use case. As usage and network effects start building, the next phase is typically opening up the ecosystem to third-parties, accelerating offline merchants and increasing consumer use cases. While most of ShopeePay’s use is currently for on-platform Shopee purchases, it has been significantly ramping its network of offline merchants.

“We are quickly expanding off-platform digital payment use cases. For example, besides increasing our payment touchpoints at convenience stores, F&B chains and on the Google Play store, our mobile wallet service recently expanded its partnership with Mastercard in Thailand. This will allow our users to pay at any of the 200,000 plus offline outlets that accept Mastercard Contactless. We are also partnering with Puregold, one of the largest supermarket chains in the Philippines, to accept our mobile wallet payment at over 400 of its stores.”

Forrest Li (Chairman and CEO), Sea’s Q2 2021 Earnings Call

Other examples of ShopeePay’s offline expansion:

F&B merchants in Indonesia such as Indomart (a leading convenience store chain), as well as Wendy's, and Domino's Pizza

In Malaysia there are over 750,000 ShopeePay touch points

In Singapore, while ShopeePay is significantly behind GrabPay in penetrating offline merchants, recently it has started aggressive promotions in various F&B chains such Boost Juice, BreadTalk and Pezza

The open-loop network is being extended to other use cases as well:

In Indonesia and Thailand there is a partnership with Google Play store which allows people to use ShopeePay as a payment method

In Malaysia, the government has been using ShopeePay to distribute assistance program payouts to youths and small businesses

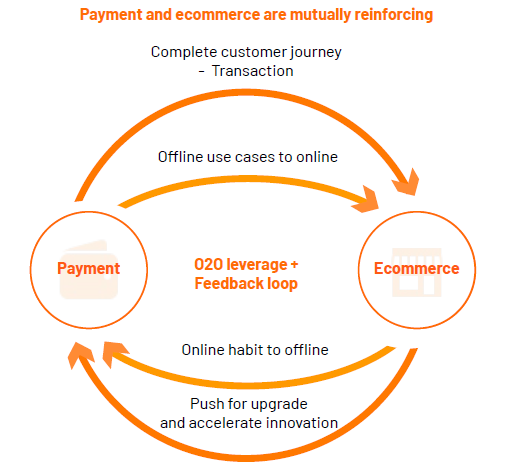

The offline and online use cases create a mutually reinforcing feedback loop: while ShopeePay usage begins on the Shopee platform, offline transactions enhance user stickiness and encourage further on-platform use.

A key driver of the e-wallet usage has been aggressive promotions and cashbacks. Sea incentivizes payment via ShopeePay by offering Shopee Coins cashbacks, which can be used to make purchases on the Shopee platform. This is an expensive strategy that comes out of the sales and marketing opex; in 2020 SeaMoney’s S&M was $415m (compared to segment revenue of $61m). However just like with Shopee, this is a deliberate scaling strategy designed to get people transacting via ShopeePay on a habitual basis, which in turn should attract more offline partners to the ecosystem.

While the cash incentives are important, the app experience itself is also critical in keeping users coming back, and there is some indication that ShopeePay is seeing success here as well:

“Even though discounts and promotions are ShopeePay’s main tactic to lure customers, Adhinegara thinks that users won’t necessarily abandon the platform once the special offers diminish. “They are more user-friendly compared to others and their offline expansion to merchants and street stalls in smaller cities is quite aggressive,”

ShopeePay tops Indonesian e-wallet game in Q1: Survey (KrAsia)

In some markets like Malaysia and Thailand, Shopee has released co-branded credit cards with bank partners, which allows users to collect Shopee Coins with every purchase.

With all of the above on-platform and off-platform efforts, usage of the ShopeePay e-wallet has grown significantly over the last two years. As at Q2’21 SeaMoney had ~33m users and is run-rating a Total Payment Volume (TPV) of $18bn. Of course with tight e-wallet competition (as discussed later), the real litmus test will be whether usage will diminish if SeaMoney was to pull back the promotions. These competitive dynamics mean that payments on its own is not enough to create a profitable fintech business.

Phase 2: Expansion into financial services

After the payments ecosystem is established and achieving scale, the next step of the evolution is to monetize the vast customer base by expanding beyond payments into other financial products such as digital lending and investment solutions. SeaMoney is at the early stages of offering other financial services, which at the moment are mainly focused around different types of lending. The exact services offered vary by region depending on consumer needs and regulatory licenses. The below tables summarises what services are available where.

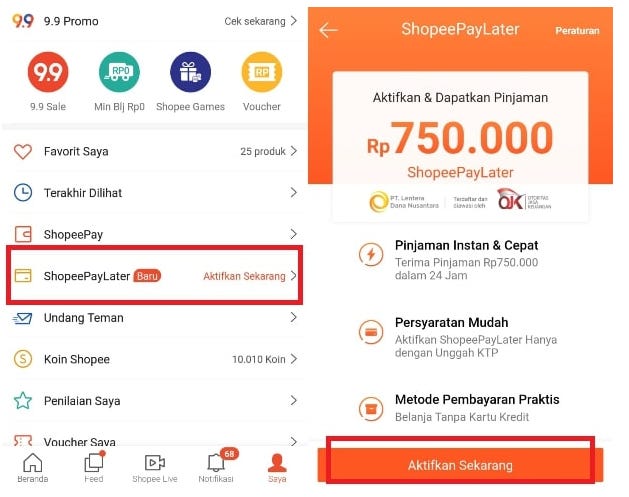

Digital banking - buy now pay later (BNPL), consumer loans, merchant loans

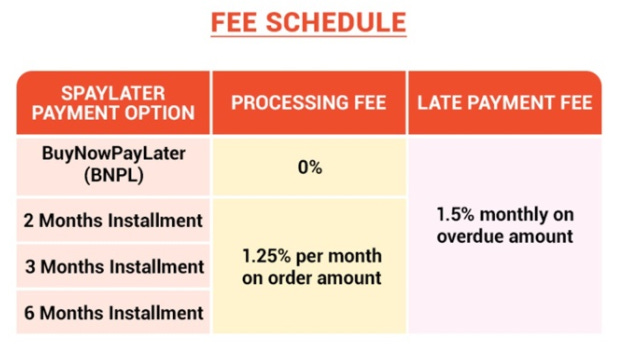

BNPL installment plans are proliferating through Southeast Asia and have proven a popular way of increasing credit adoption in emerging markets. This is because they provide a convenient and almost instant access to funds via the app. Sea currently provides this service in Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand and Philippines via ShopeePay Later. This option is available at check-out on the Shopee app, and allows the user to buy an item and pay later via instalments within six months. Interestingly unlike BNPL players in other markets such as Afterpay who monetise largely by charging a take-rate to the merchant, in Southeast Asia BNPL players monetise by charging a monthly interest rate to consumers. For ShopeePay Later, for example, this ranges from 1.25% per month in Malaysia to 2.95% per month in Indonesia2. In effect this becomes like a typical short-term consumer loan.

Together with BNPL/consumer loans, SeaMoney also lends to SME merchants to help them with short-term working capital/inventory financing or other liquidity needs. This includes providing sellers with the option to receive an advance loan on the amount that Shopee holds in each order’s escrow amount in cash. Sea currently provides these services in Indonesia and in Thailand.

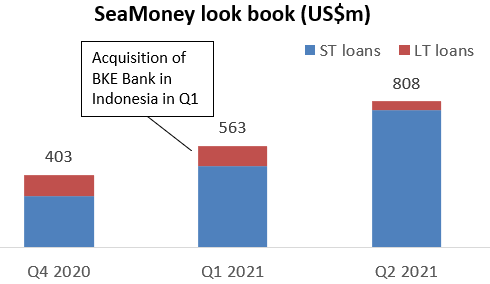

The model which Sea takes with lending seems to be both on-balance sheet and partnering with a variety of local lenders, such as KBank in Thailand. We don’t know exactly how much credit risk is taken by Sea vs. third party lenders, but typically at the nascent stages of ramping up a digital banking business, the majority of the loans would probably need to sit with Sea until their credit scoring and risk algorithm gets proven out enough to be trusted by banks. We can see from Sea’s balance sheet that their loan book has been ramping up considerably over the last few quarter.

With the on-balance sheet model, Sea would be collecting the interest revenue directly. The capital intensity of retaining loans on the balance sheet however, would severely limit scalability, so over time as Sea gets better at this operation it would make sense that it tries to shift more of its loans to bank partners. The monetisation for off-balance sheet loans is either typically a take-rate or or share in the interest of the loan amount.

In January 2021 Sea acquired a local Indonesian bank Bank BKE with the aim of transforming it into a digital bank. Acquiring a bank is quick and easy easy way to securing a bank license, although the regulator OJK recently released guidelines for digital banking which should encourage more players to apply for digital bank licenses (discussed more later). Bank BKE is a Jakarta-based private bank chain, and although small, it provides Sea with a good launchpad for scaling into the digital banking business.

In terms of other markets, Sea was one of two winners of a digital banking license in Singapore, and is expected to launch banking services there in 1H 2022. They are also bidding for a digital banking license in Malaysia, so assuming they win we should expect launch of banking services there as well. This is likely to be followed by other markets across the region.

Wealth management

While Sea doesn’t currently offer any wealth management services, this would be a natural extension of their financial product offerings. The largest opportunities in wealth management are money market and mutual fund offerings. Competitors like Grab are already offering these services, linking an auto-invest feature to their e-wallet. They offer a higher return than you would get on an average bank savings account via money market and short-term fixed-income mutual funds managed by Fullerton Funds Management and UOB Asset Management.

There are a range of other possible financial services that can be launched, including insurance products in collaboration with external partners, and trading services although that is potentially much further down the line. The more products, the bigger the ‘super-app’, the greater the ecosystem lock-in and potential customer lifetime value.

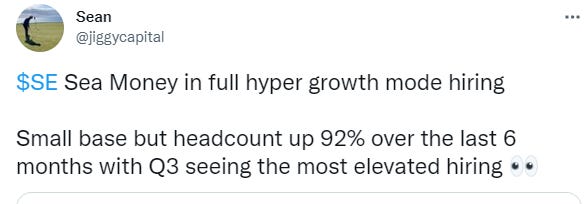

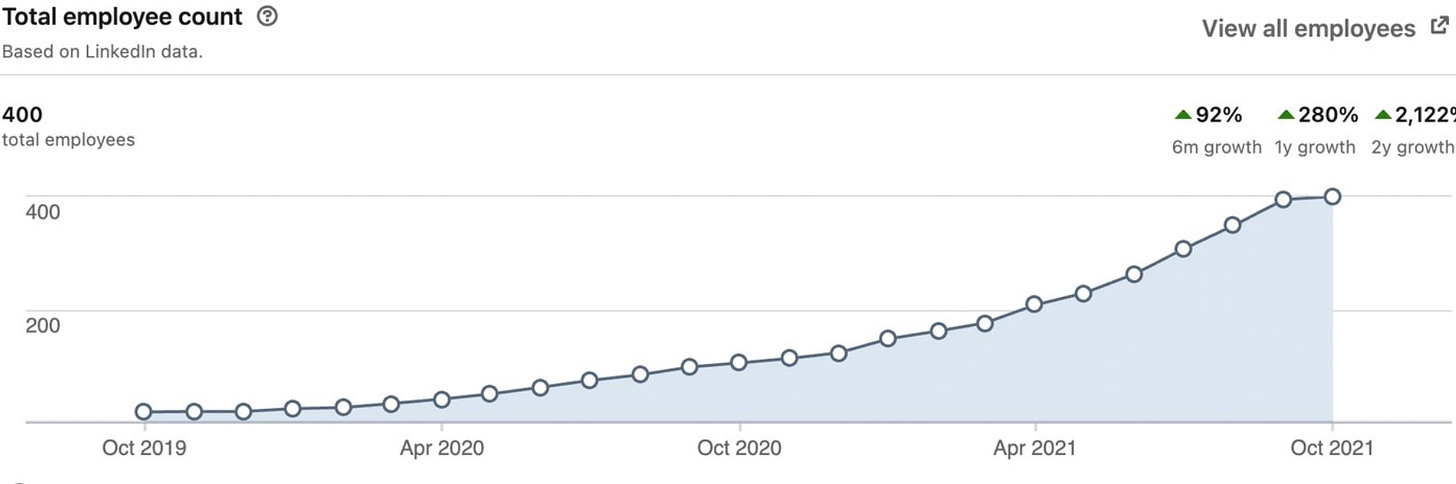

As highlighted by Sean on Twitter, Q3 has seen a surge in hiring at SeaMoney. With significant dry powder from Sea’s recent $6.5bn raise, I expect SeaMoney is going into full throttle investment mode, seeking to imitate the model that other tech giants have pioneered and is building out a full spectrum of financial products and services.

COMPETITIVE LANDSCAPE

Southeast Asia's biggest Internet companies as well as independent upstarts and traditional institutions such as banks are all vying for a share of a growing payments and digital banking arena. While the market is crowded, the opportunity is large, which means that there is room for multiple winners.

Payments

Starting with payments, and focusing specifically on Indonesia (as the largest ASEAN market), the key wallets are ShopeePay and GoPay, which are the two embedded wallets leveraging their Shopee and GoTo (Tokopedia-GoJek) ecosystems respectively. There are also major independent wallet companies OVO and Dana. OVO is now predominantly owned by Grab who recently bought Tokopedia’s 40% stake in it, and Dana is owned by Alibaba’s Ant Group and Indonesian media conglomerate Emtek. The below table from Momentum Works shows the user penetration based on surveys from different research firms.

We must always be cautious with leaning too heavily on survey data because as can be seen, different surveys produce wildly different results. What is clear is that even though ShopeePay is in a strong position, it is a tight race between them, GoPay and OVO, and there will likely be multiple winners. Bernstein’s data below shows that ShopeePay’s market share in Indonesia (also measured by surveys) is rising rapidly. As most of ShopeePay’s transaction volume is for on-platform Shopee use, its rapid rise starting from 2020 is in large part linked to the explosive growth of Shopee’s GMV, but has been supplemented by the significant offline push since Q4’19, as well as aggressive incentives via cashbacks.

In terms of off-platform penetration, it is difficult to get precise figures of who has a larger network, and the situation varies significantly by country. In Indonesia for example, OVO claims to work with over 700,000 small and micro businesses in Indonesia, while GoPay is accepted by more than 500,000 online and offline merchants. ShopeePay has yet to announce a similar number, although we know it has been aggressively expanding its presence.

There are also rumours of a potential OVO-Dana merger. Grab, who is the predominant owner of OVO, and Emtek, one of the largest shareholders of Dana, have recently made investments into each other, suggesting potential synergies moving forward. So quite likely that the market will consolidate around the wallets with the largest accompanying ecosystems, and the trio of ShopeePay, GoPay and OVO (i.e. Grab) will have the lion’s share backed by their large e-commerce and ride-hailing businesses respectively.

Digital banking

Participants in the digital bank market fall into three major categories: large domestic commercial banks (eg. BTPN, BCA in Indonesia), pan-Asia regional banks (eg. Singapore’s DBS, UOB, OCBC), as well as tech players (e.g. GoTo, Sea).

Again it is difficult to measure market share in this space accurately, so we have to rely on metrics like app downloads and consumer surveys to get sense relative strength. According to app download data below from Momentum Works, the digital banks owned by commercial or regional bank players have been seeing strong growth. Jenius, a digital bank launched by local bank BTPN, is currently in the lead, followed by OCBC’s Nyala, PermataBank’s Me, and DBS’s Digibank.

However, the above data wouldn’t capture Sea or GoTo’s market share as they would be distributing loans via their own apps (Shopee, GoJek respectively), rather than a separate digital banking app. The below survey data from Bernstein however, helps us get a sense of how they are placed vs. peers.

As can be seen, generally it corroborates the view from app downloads that digital banking arms of local commercial/regional banks (Jenius, Blu, Digibank) have strong brand awareness. Interestingly the GoTo-aligned Bank Jago ranks highly as well, while SeaBank is still at a very early stage and some way down the list.

As mentioned earlier, Sea recently bought local bank BKE Bank to kickstart its digital banking operational in Indonesia. GoTo bought 22% of of Bank Jago, a large local banking franchise, late last year. Soon GoTo offer fully integrated banking services to customers directly via the Gojek app. People will be able to fully open accounts via the app, using the cash on their e-wallets as their first deposit, be able to make cash deposits at convenience stores, receive Visa debit cards, be able to access credit through BNPL schemes, and access investment options such as index funds. Other perks will include discounts on products sold on Tokopedia. GoTo also plans to offer similar banking services to SMEs. Other tech players competing in digital banking include Alibaba-backed Indonesian fintech startup Akulaku, who became largest shareholder in Bank YudhaBhakti, which later changed its name to Bank Neo Commerce. Japan’s Line Group, which operates the popular messaging app Line, also announced it will be entering digital banking through a 20% stake in a local lender. Standard Chartered and Bukalapak are preparing to launch digital banking services on the latter’s e-commerce platform. And, Grab and Emtek Group are reportedly investing in a local lender called Bank Fama to build their own digital bank. Essentially there is no shortage of tech players entering the digital banking space, usually in collaboration with traditional banks.

Overall the market is still very early, and I expect that even more competition will emerge, particularly as countries develop digital banking frameworks. As typically happens after the initial rush of entrants, consolidation will inevitably take place. It is still too early to tell who will come out on top but there is definitely room for multiple winners.

SeaMoney is in a good position to build out a dominant business leveraging the Shopee ecosystem, and its access to Garena’s organic cash engine provides it with a unique advantage vs. the likes of GoTo and Grab. It is able to focus aggressively on scaling this business without having to worry about monetisation too early, whereas the other major players do not currently have profitable core businesses and need to keep relying on external funding, which may inhibit their potential to scale. Sea’s ability to bear the cash burn required to build out an adjacent fintech business is therefore much higher.

CASE STUDY: MERCADOPAGO

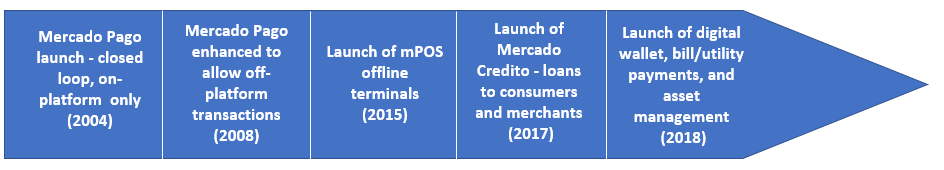

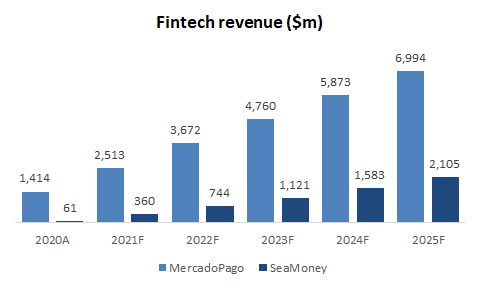

MercadoLibre’s fintech business MercadoPago provides a perfect example of how a financial services business of an e-commerce company can scale up, leveraging the strong growth in e-commerce GMV. MercadoPago is expected to bring in ~$2.6bn of revenue this year and is growing at a 40%+ CAGR. SeaMoney is following a similar roadmap for its growth but is much earlier in its lifecycle, and thus MercadoPago a useful case study of what SeaMoney could look like in a future state.

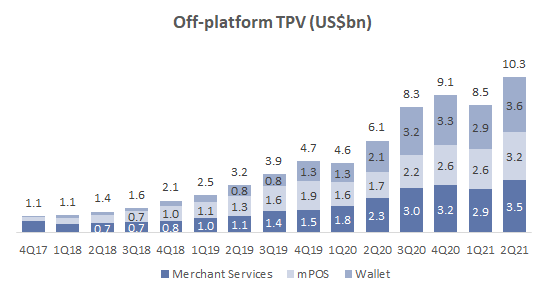

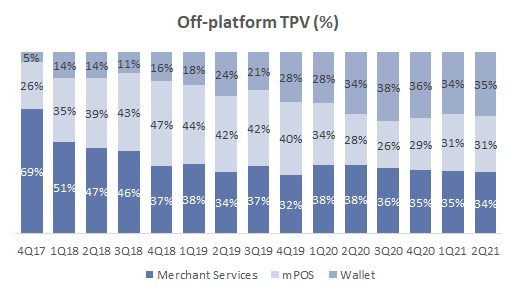

MELI initially launched its payment processing services mostly to facilitate secured transactions on the MercadoLibre marketplace in 2003, named as MercadoPago. In 2008 MercadoPago launched an enhanced version of its platform which allowed integration with off-platform merchants. It allowed merchants who are not registered with the MercadoLibre Marketplace to receive payments, as long as they are registered with MercadoPago. In 2015 it launched a mobile Point of Sale (mPOS) solution, machines that allow merchants and consumers to process physical credit and debit cards, which significantly helped to drive their offline payment volumes. As MELI continued to invest aggressively in expanding merchant adoption, off-platform transaction growth significantly outpaced that on-platform. Between FY15-17 off-platform accounted for 20-24% of TPV. Since then it has grown to account for the majority (>60%) of total TPV. Given that off-platform transactions generally earn a higher take-rate for the company, this is a great example of how to create a scaled and profitable open-loop payment network.

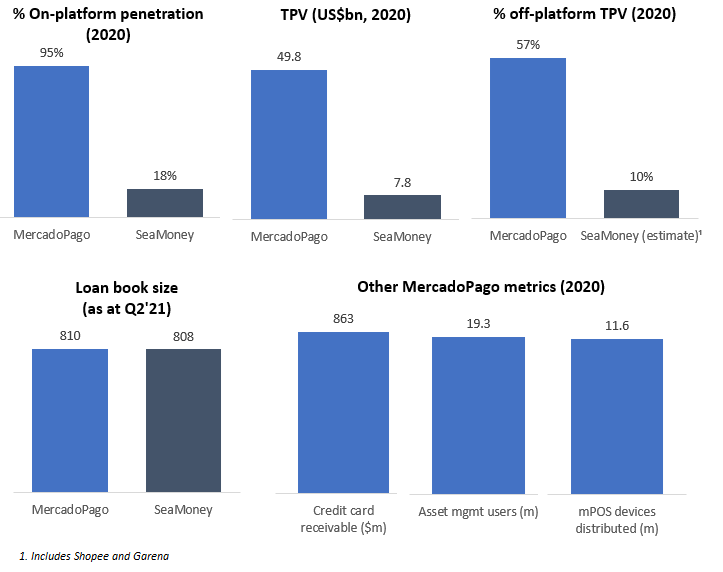

The main takeaway from the scale up of MercadoPago is that as the marketplace achieves scale with penetration of in-house payments increasing its share of on-platform transaction (~95% for MELI), offline merchant acceptance follows, particularly in geographies with large underbanked populations such as LATAM.

Cutting the off-platform TPV data another way, we see that with the scale up of mPOS share (as MELI has distributed millions of mPOS terminals), e-wallet share of offline transactions have also seen an uptick for MELI. There is a mutually reinforcing flywheel between all of these elements of their payments business. Both of these these initiatives has helped MELI to increase its off-platform TPV from $0.6bn in 2012 to ~$30bn in 2020.

One important thing to note is that the competitive landscape in digital payments was not as intense in LATAM when MercadoPago opened up its payment solutions to off-platform merchants, and it was largely the only player offering a large e-commerce marketplace accompanied with e-wallet service. This gave MELI a significant first-mover advantage in scaling up its offline merchant base. In the case of Sea, the e-wallet market is already competitive in Southeast Asia as the other e-commerce and ride-hailing giants have their own e-wallets or have collaborated with independent wallet providers. This may mean that the scale up of off-platform wallet services may not be as rapid for SeaMoney.

In 2016 MercadoPago launched consumer and merchant lending, Mercado Credito, relying on machine-learning algorithms to determine a more accurate scoring for each user. Mercado Crédito provides credit access to consumers, enabling them to buy either on the platform or in store from MELI’s merchants, including mPOS merchants. The loan book has grown significantly, as shown below. As at Q2’21, their loan book was $810m, with a recent skew towards consumer loans. Surprisingly despite MELI’s significant headstart, its loan book is currently the same size as SeaMoney’s, which shows how aggressive Sea has been in ramping its lending business (boosted by the acquisition of BKE Bank).

In 2018 MercadoPago launched an e-wallet which facilitated payments, QR codes, mobile top-ups, bill payments (eg, utilities), money transfers (wallet-to-wallet and cash-out). It also launched a mutual fund service called Mercado Fondo, which allows excess funds in the wallet accounts to be invested in funds managed by the Buenos Aires-based Banco Industrial SA (Bind). This e-wallet linked asset management service has seen significant success with now over 19m registered users.

Below is a side by side comparison of the key metrics between MercadoPago and SeaMoney. It really highlights the different stages of maturity of their businesses and how much room to scale Sea has.

Finally, the differences in revenue highlight just how nascent SeaMoney is compared to MercadoPago. As we can see below, SeaMoney is just beginning its monetisation journey, and even by FY25 I am assuming that SeaMoney is still smaller than MercadoPago today. Assuming SeaMoney can achieve even a fraction of MercadoPago’s success, the growth runway is clearly very large.

FORECASTS AND VALUATION

Revenue forecasts

It needs to be said upfront that of all Sea’s businesses, SeaMoney is the one with the least disclosure and thus is by far the most difficult to model. Even research analysts who I have spoken to cannot fully grasp its revenue composition. What I have laid out below is my best attempt at breaking down its revenue drivers, triangulated from various public disclosures and industry data points. No doubt I will probably be revising these over time as more information about the business is provided.

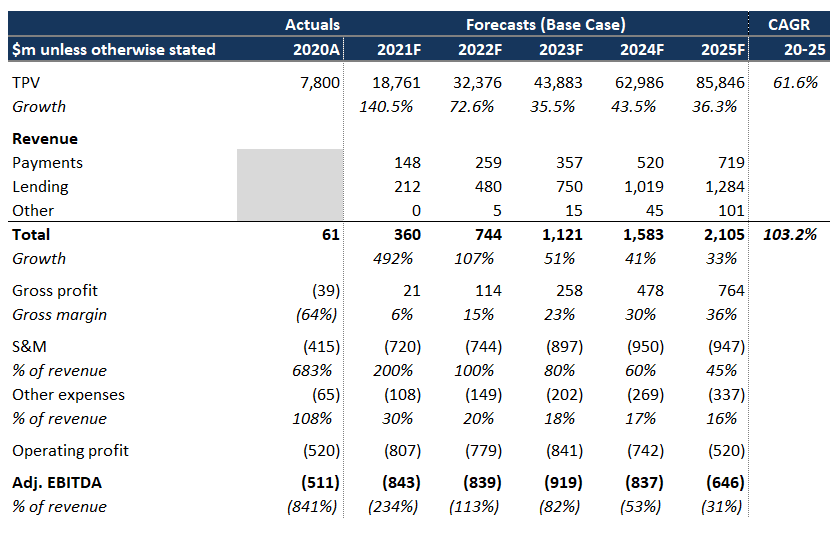

I have assumed there are three key revenue segments: Payments, Lending, and other financial services. As can be seen above, I expect the revenue to be largely split between payments and lending, with some nominal contributions to come from other services.

Payment revenue: The key driver of payment revenue is TPV, both on-platform (Shopee/Garena), and off-platform (external 3P offline merchants). We need to make some assumptions around the mix between on and off-platform. Most estimates are that for 2020 about 10% of Sea’s TPV was off-platform. This should increase as Sea ramps up offline merchants, and I have assumed it can get to 35% by FY25. As shown earlier MELI is currently at over 60% off-platform, however due to the tougher e-wallet competition in Southeast Asia I assumed SeaMoney’s offline ramp will take longer.

For the on-platform portion, we need to assume what proportion of Shopee’s GMV and Garena bookings are transacted through ShopeePay/AirPay. For 2020, this proportion was estimated to be around 18%. I have assumed this increases to 40% by FY25 as more people adopt e-wallets due to cashback incentives and habitual use. As a comparison, almost 100% of MELI’s GMV is transacted through MercadoPago. The GMV for Shopee and Garena bookings are as per my forecasts from my earlier articles.

Finally we need to assume the fees or take-rates charged on the payment volume, which will be different for on-platform and off-platform. From what I could find on-platform fee rates charged to merchants are between 0.6-1.2% - I have assumed 0.75%. The take-rates for off-platform merchants are likely somewhat higher, estimated to be around 1% based on various Sea disclosures. Due to competitive pressure and e-wallets being somewhat of a commoditised business, I don’t expect there to be any pricing power to increase these take-rates over time, particularly as Sea prioritises building scale over the next few years.

Based on the these assumptions, TPV is estimated to grow from $7.8bn in 2020 to $85bn by FY25, and associated payments revenue is estimated to grow from $148m in FY21 to $719m by FY25.

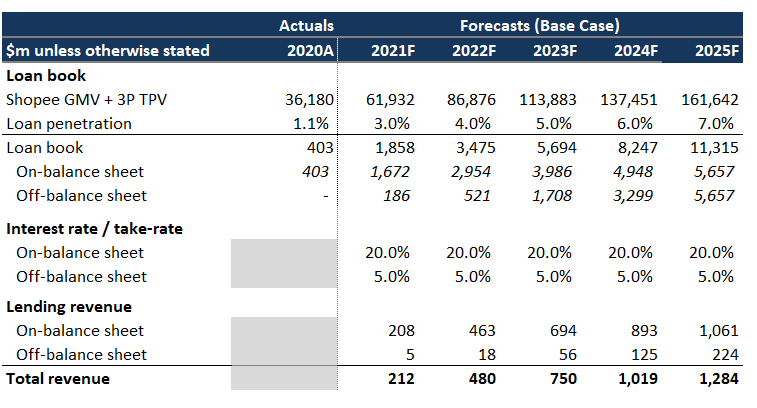

Lending revenue: Since it is impossible to know the split between BNPL/consumer/merchant lending, I have modelled this segment on a whole-of-loan book basis. It is probably a reasonable assumption that majority of lending will be linked to Shopee transaction value, whether BNPL or merchant lending against order escrow accounts, but there would also be some lending against off-platform payment transactions. So I have modelled the growth of the loan book as a penetration of Shopee GMV plus off-platform TPV (as per above). Based on current trajectory of loan book growth, I have assumed that for FY21 3% of Shopee GMV+ off-platform TPV is converted to loan book, which amounts to ~$1.7bn by year end (as at Q2’21 it was $808m, at Q1’21 it was $563m). I have assumed this penetration grows to 7% by FY25, or $4.2bn of total loans.

There is a bit more nuance to this however, as the monetisation will depend on whether the loans are on Sea’s balance sheet (self-funded) or off-balance sheet (funded by bank partners). I have assumed that for FY21, 90% of the loans are on Sea’s balance sheet, as I think that is typically what would need to happen at the nascent stages of a fintech player building out its lending business and needing to prove that its credit-scoring and risk management algorithm works. As this is proved out though and bank partners get more comfortable taking credit risk for Sea, the loan exposure would likely shift over time to the banks, in turn improving the scalability of the business due to better capital efficiency. I have assumed that the on-balance sheet portion can shrink to 50% by FY25.

Next we need to estimate the interest revenue on the loans. The interest rate on the on-balance sheet loans should be higher than the take-rate on off-balance sheet due to greater credit risk that Sea is taking. We know that for BNPL, Sea charges between 1.25% (Malaysia) to 2.95% (Indonesia) per month for instalment periods of greater than one month. Annualising these monthly rates, a 20% interest rate could be a reasonable assumption. This also corroborates with the reported interest rates in the filings of listed digital bank Bank Jago3. I have assumed that this 20% applies to the entire on-balance sheet loan book, regardless of whether its BNPL, consumer loan or merchant loan (given the similar customer profile and predominantly short-term financing nature of all these loans I have assumed that the risk profile is broadly similar). For the off-balance sheet loans, I have assumed a 5% take-rate. Based on the these assumptions, interest revenue is estimated to go from $212m in 2021 (estimated) to $1.3bn by FY25.

Other financial services: While SeaMoney doesn’t really have any services outside of payments and lending currently, it is quite likely it launch other services following the playbook of various other tech companies. This could include wealth management/investments, insurance, and trading. I have not modelled these out in any detail but have just assumed a nominal contribution of $5m of revenue starting in FY22 and growing to $100m by FY25, which is only about 6% of total SeaMoney revenue

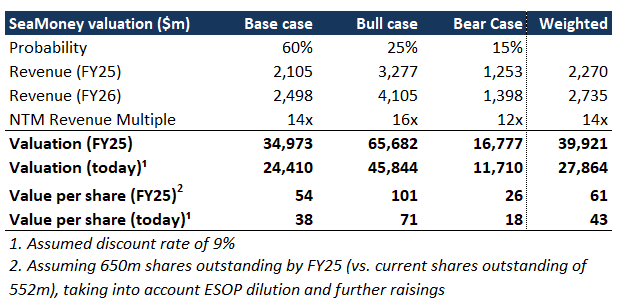

Bull and Bear Cases

There is significant uncertainty with forecasting a high-growth fintech business like SeaMoney. Given the wide range of potential outcomes, I have also run bull and bear cases, which I then combined with my base case in a probability-weighted valuation. The key difference between each case is largely linked to the bull and bear scenarios of my Shopee and Garena forecasts, since I am assuming that SeaMoney’s payments and lending revenue is symbiotically linked to the fates of these businesses, particularly Shopee. I have also assumed a higher/lower penetration of e-wallet payments of on-platform GMV and off-platform merchants in the bull/bear cases respectively. As can be seen, it results in a fairly wide range of FY25 revenue outcomes, from $1.25bn to $3.3bn.

Profitability

There are several dynamics that I believe will make profitability for this business challenging over the forecast period. Firstly, e-wallet payments is somewhat of a commoditised business which as explained earlier is highly competitive in Southeast Asia. Thus I believe no player can really charge take-rates significantly above cost recovery (funding the wallets would incur payment processing costs for Sea). Off-platform payments, while I believe have more potential due to higher take rates, should also not be significantly profitable due to tight competition. This means that gross margin contribution from payments will be quite low - I estimate no more than ~10% over the next few years.

That means that value generation should really come from digital lending and other value added financial services offerings. While BNPL and micro-financing is also somewhat of a commoditised business as well, it is possible for an operator to gain cost advantages against competitors through scale. Gross margins for lending (or effectively net interest margins) could be potentially very large as a sensible micro-financing operation is characterised by low cost of funding (usually deposit rates which are very low) and relatively high yields on loans underwritten. For instance, the aforementioned Bank Jago, which is one of the larger digital banking operations in Indonesia, has deposit rates are in the range of 3-4%, vs. their average lending rate of 15%. It’s reasonable to assume that Sea’s Bank BKE would have similar net interest spreads, but also a large portion of Sea’s loan book would not be funded by deposits but by its other sources of low cost capital (such as its convertible notes). This makes calculating the gross margin a bit tricky but I have assumed that 50% gross margins on lending should be possible by FY25. This should help lift the overall gross margin of the group rising from virtually zero today to ~35% by FY25.

Similar to the dynamics of the Shopee business, achieving insurmountable scale is of utmost importance and by being part of a cash-generating business, SeaMoney is able to focus on scale and not stunt network effects by monetizing too soon. As part of that strategy, SeaMoney is spending aggressively on sales and marketing, largely in the form of discounts and cashbacks to promote the use of the ShopeePay wallet. In 2020 S&M was $415m, multiples higher than SeaMoney’s revenue that year of $61m as the business is still sub-scale. I have assumed even higher S&M spend over the forecast period as the business seeks to scale up its volumes aggressively, and although there will be some operating leverage, I expect that this large opex will prevent SeaMoney from being EBITDA positive even by FY25.

Valuation

Given that SeaMoney is not profitable, the business is generally valued on revenue multiples. Looking at the 5-year average rolling NTM revenue multiples of global fintech/payment comps such as Visa, Mastercard, Square, Adyen and StoneCo, the average multiple is around 15x NTM revenue. I think the more relevant comparable to SeaMoney given the e-commerce to fintech cross-over is the valuation prescribed to MercadoPago by brokers in MELI’s SOTP valuations - this is typically in the 14-21x NTM revenue. Triangulating both of the above benchmarks, I believe a 14x NTM Revenue is an appropriate multiple for valuing SeaMoney in its more mature FY25 state under the base case. The bear case I have pegged at 12x and the bull case at 16x to account for the slower/faster growth respectively in these scenarios. The resulting probability-weighted valuation is below:

In the base case I am deriving a valuation of ~$24bn if discounted to today , or $38 p/share. However we can see that the range is pretty wide; between $12bn ($18 p/s) to $46bn ($71 p/s). Based on management’s consistent track record of outperformance to date I would think that my bull case is more likely than the bear case. Thus I’ve assigned a slightly higher probability weight to the bull case than the bear case (bull case p = 25%, base case p = 60%, bear case p = 15%). Probability-weighting the different scenarios I get a weighted valuation of ~$28bn if discounted to today, or $43 p/share today.

I will go through my overall Sea Group valuation and IRR calculations in my next and final article.

CONCLUSION

SeaMoney has grown from the background to become a critical part of the Sea growth story. It is a synergistic piece that creates value for the entire group by reducing payment friction and increasing customer stickiness and lifetime value. However, there is a tremendous opportunity to create a much more valuable fintech franchise by building an entire online-to-offline payment ecosystem and value-added financial services, a la MercadoPago.

While the market is definitely competitive with no shortage of players both on the payments and digital banking side, the ability to leverage the large Shopee ecosystem and access to Garena’s organic cash engine provides SeaMoney with a unique advantage vs. the competition. It is able to focus aggressively on scaling and building out the essential network effects without having to worry about monetisation or profitability too early. This puts it in a strong position to become one of the winners of this rapidly growing market.

If you made it to the end, thank you for reading and hopefully you found the article helpful. I welcome all feedback, good or bad, as it helps me improve and clarifies my thinking. Please leave a comment below or on Twitter (@punchcardinvest).

Also if you’d like to receive Parts 4 of my Sea deep dive as it’s published, or future deep dives on other tech companies, please subscribe below.

For further reading on SeaMoney, payments and fintech:

Momentum Works has exceptional coverage of the Southeast Asian fintech and digital banking space. I recommend the below reports:

Future of Asia: The Future of Financial Services, (McKinsey & Company)

Fintechs and traditional lenders do battle across Southeast Asia (Nikkei Asia)

Indonesian financial regulator releases blueprint for digital banking (KrAsia)

ShopeePay tops Indonesian e-wallet game in Q1: Survey (KrAsia)

Asia’s Tech Juggernauts Zero In On Indonesia’s Digital Banking Market (Forbes)

Southeast Asia has seen the development of national account-to-account (A2A) real-time payment systems such as PayNow in Singapore, DuitNow in Malaysia, and PromptPay in Thailand

Bank Jago reports an average lending interest rate of 15%

Hi, Sea just announced Q3 result, while Shopee and seamoney remains strong growth, GARENA business was a bit slown down (QAU growth was slown), does the result meet your expectation?